A Black Methodist voice from the past has much to teach us about how to be a messenger of both judgment and grace to a church moving toward racial justice.

REV. DR. CHRIS MOMANY

Dowagiac: First UMC

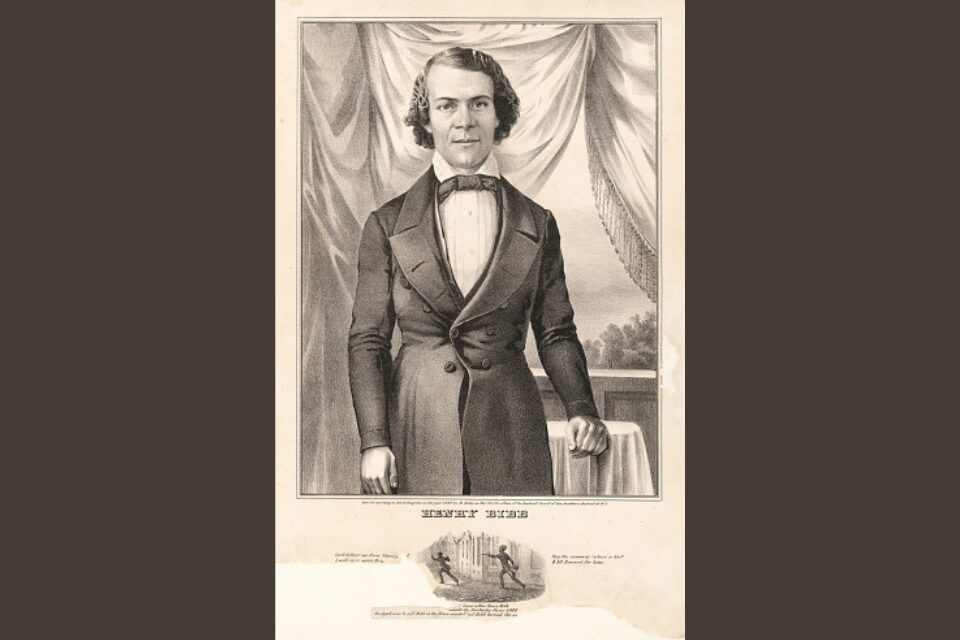

Much is made of John Wesley’s uncompromising opposition to slavery. Yet in July of 1839, Methodist Henry Bibb escaped bondage in Kentucky and soon found himself surrounded by a mob. The thugs forced him back to a plantation, and he later recalled: “In searching my pockets, they found my certificate from the Methodist E. Church, which had been given me by my class leader, testifying to my worthiness as a member of that church.”1 Shamefully, many in the mob were from the same Methodist congregation, and the man who claimed to “own” Bibb was also a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church.2

After several years, Bibb finally escaped for good and arrived in Detroit in 1842. Before long, he was asked to speak about his painful experiences. The address took place in Adrian, Michigan, and Bibb wrote: “The first time that I ever spoke before a public audience, was to give a narration of my own sufferings and adventures, connected with slavery.”3 He became a regular lecturer for the Michigan State Anti-Slavery Society, but simply narrating his story did not satisfy Bibb. He wanted to attack slavery and all oppression through incisive logic and compelling speech.

By 1846, Bibb was articulating an intentional vision of freedom. He wrote for the Michigan publication Signal of Liberty and argued: “Consistent action is the key to emancipation.”4 Bibb’s invocation of both principle and action integrated two things that were rarely mentioned in basic narratives about slavery. He wrote not only about his experience but about the meaning of his experience and what that experience could offer. He wrote about ideas and their motivating power, and then he urged action in conformity with those ideas. He certainly possessed a voice now, but he also supercharged that voice by using it to express life-giving principles and by articulating concrete steps toward justice.

In 1850, the United States Congress approved a provision that was known as the Fugitive Slave Law. This heinous legislation made it a federal crime to assist people on the Underground Railroad. Soon, people of color gathered in Sandwich, Canada West (now Windsor, Ontario) to form a society that would welcome and support expatriates from the United States. Bibb was a key figure in this movement.

A resolution from one meeting called for the creation of a printing press and for a publication that would promote the settlement in Canada. The language was stirring: “As we struggle against opinions, our warfare lies in the field of thought . . . .”5 Again, ideas mattered, and a medium for the exchange of ideas and the advancement of them was necessary. This determination to publish a newspaper bore fruit on January 1, 1851, when the Voice of the Fugitive appeared. Bibb edited the paper until less than a year before he died in 1854.

One subject addressed in Bibb’s paper was the residual tolerance of slavery among northern Methodism. Even today, many presume that following the split of mainline Methodism in 1844, northern expressions of the movement were admirably free from slavery. This is not quite so. Bibb let it be known that the Methodist Episcopal Church (North) remained complicit.

The June 18, 1851, issue of the Voice carried a lengthy article with this provocative title: “Is the M. E. Church of the North Pro-Slavery?” Bibb cited the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society Report for May 1851.

This document acknowledged that most Methodist compromise with slavery happened in the South. Yet it also held the northern branch of Methodism up for critique. Some congregations affiliated with the Methodist Episcopal Church (North) were in the South, and some of these churches participated in slavery. This same report observed: “Much remains to be done in the M. E. Church North even, before it comes up to the standard of its illustrious founder, whose most matured sentiment, fearlessly announced, was, ‘SLAVERY IS THE SUM OF ALL VILLAINIES.’”5 Henry Bibb lived by the conviction that honesty was a necessary component of authentic justice.

In our day, many equate criticism of America’s behavior with an attack on its foundations. If one wants America to be better, to be more just, that is often mischaracterized as a lack of patriotism. If one holds out a mirror to the church and names inconsistencies or sins, that person is often labeled a malcontent. However, Henry Bibb did not hate America when he left for Canada. He grieved for America. He did not take delight in confronting Methodism. He wanted his movement to keep John Wesley’s founding vision. We have much to learn from him and his ability to experience brutalizing marginalization while also encouraging the better angels of his world.

Henry Bibb was a messenger of both judgment and grace, and we can be grateful for his presence among the witness of Michigan Methodism.

1 Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, 87.

2 Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, 84-87.

3 Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, 178.

4 The Signal of Liberty, 6, no. 24, 93.

5 “Fugitive Slaves in Canada West,” Voice of the Fugitive, 1, no. 1, 2.

6 “The Annual Report of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, Presented at New-York, May 6, 1851,” 41.

Chris Momany is a former chaplain and professor at Adrian College. He is the author of three books, including his latest, Compelling Lives: Five Methodist Abolitionists and the Ideas That Inspired Them (Cascade Books, 2023). The story of Henry Bibb is featured in this book. He is a founding member of the Dialogue on Race and Faith, which will release its book on racial justice in March of 2024: Awakening to Justice: Faithful Voices from the Abolitionist Past (InterVarsity Press).

Event notice: On Tuesday, March 5, 2024, from 9:30 am to noon, Momany will lead a workshop at the Wesley Foundation of Kalamazoo on The Gospel of Love and the Work of Justice, which is based on his book Compelling Lives. Anyone willing to grow personally and work for justice should plan to attend this free event. Click here to learn more and to register.

Last Updated on February 28, 2024