The Rev. Bill Wylie-Kellermann reflects on the prophetic ministry of Pastor Daniel Berrigan, his spiritual director for half a century, whose witness speaks to today’s headlines.

BILL WYLIE-KELLERMANN

Retired Pastor, Michigan Conference

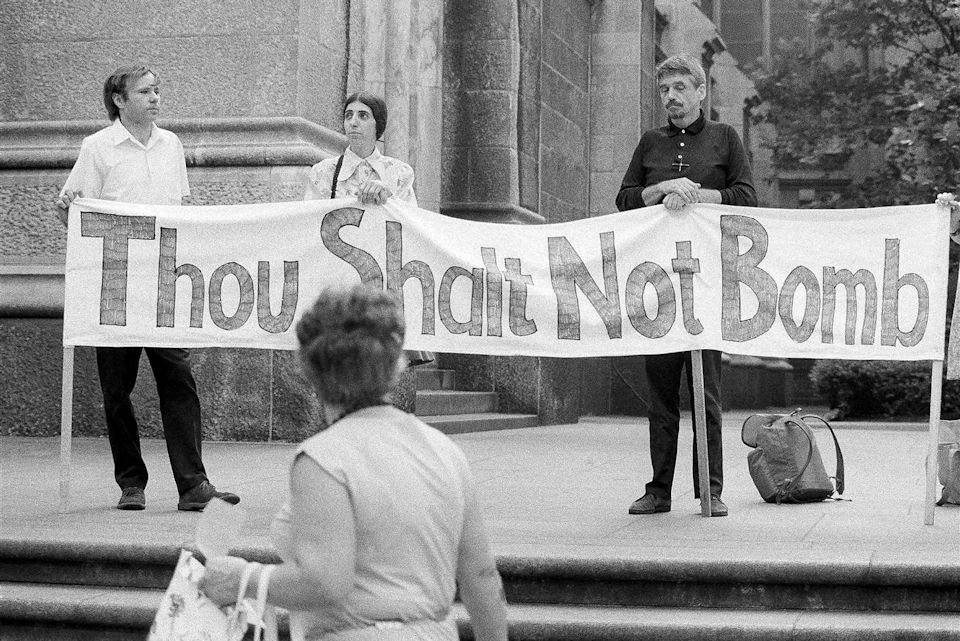

Fifty years ago, at Union Seminary New York, Daniel Berrigan (+2016+) as he came out of Danbury Federal Prison, became to me a spiritual director, before I even knew there was such thing. I can testify that his pastoral gifts were unaccountably great, though he is better known for prophetic ministry in burning draft files in 1968 as a protest against the U.S. War in Southeast Asia, or for his equally costly liturgical actions against subsequent wars and nuclear weaponry.

But side by side with these, Dan was tending the dying. Like Camus’ doctor in The Plague, he tended victims while saying No to the executioners.[1] In the ’80s he sat to the end with AIDS patients, the untouchables ravaged by both disease and culture. I have notes from him on cards depicting Christ crucified by AIDS. In Sorrow Built a Bridge[2], he recounted, eyes wide open with love, their crossings over.

Earlier, this pastor had done the same at a hospice for the dying in Manhattan—specifically, the dying poor with cancer. Needless to say, he made the connections—they were woven whole cloth into his life. He recognized Hiroshima as the emblem of unleashed fallout in culture, history, planet. Genes corrupted by the radioactive poisoning of water and air were simply to be seen as the ailment of this world. Cancer? They declare war on that, too. The targeting of civilians in atomic bombing flowed from the long-time casting off and casting out of the poor. All one before the war god Mars.

Berrigan also told their stories. We Die Before We Live[3] reads partly like a journal, feeling his way forward in the hospice halls, learning the clumsy arts of touch or silence or a word, all prayer. But largely the book collects vignettes, accounts of the dying, their ways and faces.

Dan had been led to the hospice by a young Catholic Worker serving there as an orderly. I suggest the influence of the Worker here in a further way. Going back to the days of Dorothy Day, the New York paper had a practice, picked up by others around the country, of eulogizing guests who would ordinarily cross over in the silence of blank and nameless obscurity.[4] Often as not, sizing up characters fit for a Dickens novel, these descriptions could be funny and heroic and quirky, but above all honest and loving. I always read them. This pastor knows the style crept into my own approach to doing funeral liturgies.

If you find the gospel in someone’s story only by smoothing the facts, then it’s really less than truly human and actually less than the gospel as well. Consider how too often a pastor uses conventional burial liturgy is taken up with such smoothing and fluffing as denial. Or saying carefully, in effect, nothing at all. Face-painting a corpse. Anyway, thanks be for the humor, poignancy, and refusal to look away, evinced by those tales

In 1985 Pastor Berrigan preached theologian William Stringfellow’s eulogy on Block Island. Beside a culture of betrayal, political, economic, spiritual, in the nation and on the Island, he set Bill as a non-betrayer, a keeper of his word, indeed the Word of God. He declared:

A sophisticated people is struck by a shortage of words adequate to describe a bad time and how one might meet it. So we grope with negatives- non-violence, non-compliance, non-betrayal. In such a time, friendship is reduced to the bone. It becomes a matter of non-betrayal. Stringfellow saw betrayal on all sides (as indeed all but the purblind must see)- the large betrayal of public trust, public monies, the public compact…What was manifestly impossible in public life he created and cherished up close…There could exist in such a world a community of non-betrayal, non-cooperation, non-surrender. It required that the members enter a covenant, say their prayers, gather and then scatter to their work, and above all, the first of all, cherish one another… My encounter with this spirit of Stringfellow and his non-betraying friendship dates notoriously from 1970 and events that occurred up the road from this chapel. I was lifted from the home of Stringfellow and trundled off the Island into prison… But for those few days, Stringfellow’s home was the only church I knew. It was the only safe place in the universe. And this was the aspect of Christ that this Christian kept opening before his friends. Christ was our friend, in such a world, in such a lifetime as ours, precisely because He does not betray. He keeps covenant, He keeps His Word, even with us, even when we break covenant, break our word, betray… For thousands of us, [Stringfellow] became the honored keeper and guardian of the Word of God, that is to say, a Christian who could be trusted to keep his word, which was God’s Word made his own…And that Word he kept and guarded and cherished now keeps him. This is the way with the Word, which we name Christ. The covenant keeps us who keep the covenant.[5]

Long before, at a festival of hope during the 1968 Catonsville draft files trial, Stringfellow—weak and frail with extreme illness—had climbed the pulpit to utter, by Dan’s account, a single terse testimony: “Death shall have no dominion!” The congregation rose in a standing ovation.

~ Excerpt adapted from Bill Wylie-Kellermann, “Celebrant’s Flame: Daniel Berrigan in Memoir and Reflection” (Eugene OR: Cascade Publishers, 2021); top photo Creative Commons

[1] See Bill Wylie-Kellermann, “Orderly of Nonviolence: With Camus in the House of the Dying,” in Celebrant’s Flame: Daniel Berrigan in Memory and Reflection (Eugene, OR: Cascade Publishing, 2021)

[2] Daniel Berrigan, Sorrow Built a Bridge (Fortcamp Publishing, 1989), reprint (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock).

[3] Daniel Berrigan, We Die Before We Live, (New York: Seabury, 1980)

[4] See Amanda W. Daloisio, Dan Mauk, and Terry Rogers, eds. Ambassadors of God: Selected Obituaries from The Catholic Worker (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2018).

[5] Daniel Berrigan, “A Homiletical Afterword,” in Bill Wylie-Kellermann, ed., William Stringfellow: Essential Writings (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2013), pp. 231-4.

Last Updated on October 31, 2023