The DRF (Dialogue on Religion and Faith), a team of abolitionist scholars, recently gathered to study a journal written in 1839 by David Stedman Ingraham. The group includes Michigan pastor Chris Momany.

GLENN M. WAGNER

Michigan Conference Communications

This is a story about a great treasure . . . more important than money. This treasure remembers fact, is an eyewitness to a significant life-shaping event and communicates life lessons worthy of passing along to future generations. This treasure is inspiring scholarship with hopes of changing lives.

In the 19th century, Asa Mahan decided to hold onto the personal hand-written journal he had received from a like-minded protégé, David Stedman Ingraham. Mahan was the first president of Adrian College, founded in 1859, two years before the American Civil war. Adrian College, one of two United Methodist-affiliated colleges in Michigan, located in Adrian, 73 miles southwest of Detroit, opened intentionally with what was then a radical idea to provide Christian higher education for persons of any race and gender. Adrian College was founded by abolitionists influenced by Christians with anti-slavery sympathies from Oberlin College in Ohio.

When Adrian College received its first student, David Ingraham’s journal was already 20 years old. Ingraham had written the journal between 1839 and 1841 in Jamaica, where he was serving as a missionary. Unfortunately, Ingraham died in 1841 from tuberculosis at the age of 29. Nevertheless, the journal, which survived as witness to his brief but important work, was deemed worthy of saving and found its way into Mahan’s possession.

David Ingraham was a member of the first parish served by Asa Mahan near Rochester, NY.

When Asa and Mary Mahan moved to Cincinnati, OH, they led a church in the city. Mahan also became a member of the Board of Trustees of Lane Presbyterian Theological Seminary. David Ingraham moved to Cincinnati after the Mahan’s were already established. Ingraham joined Mahan’s congregation and also attended Lane Seminary to prepare for a life of Christian service.

David Ingraham, originally a native of Wayne County, MI, was also part of a group of students at the seminary passionate about the anti-slavery abolitionist movement who left Lane in rebellious protest over the school’s pro-slavery sympathies. Mahan was remembered to be the Board member at Lane who sided with the students. That may explain how he was eventually entrusted with this precious journal. Ingraham transferred from Lane to complete his education at Oberlin College in Oberlin, OH, which had inclusive admissions policies and anti-slavery sentiments.

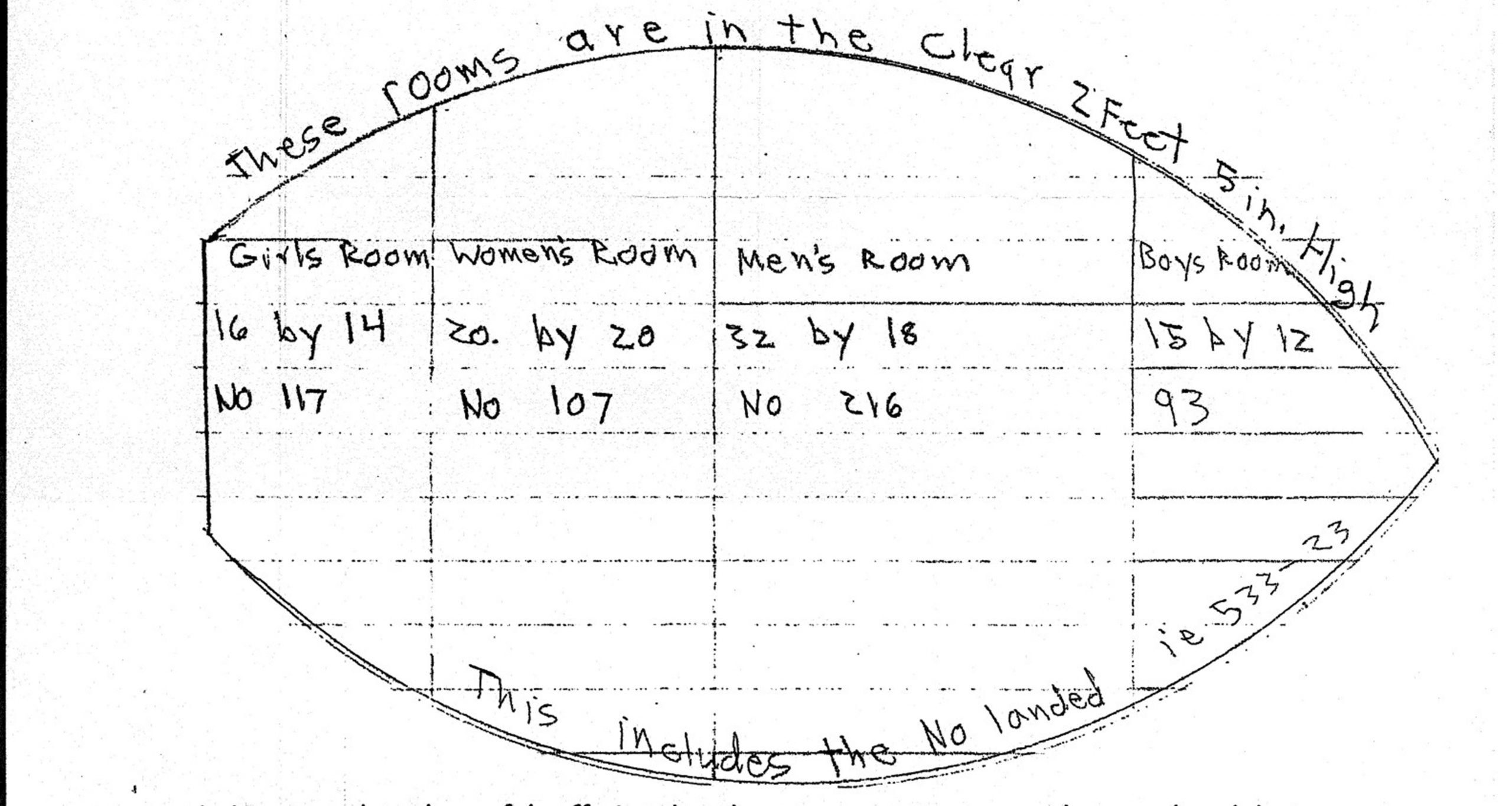

Ingraham’s journal includes a rare sketch of the interior compartments of a slave ship, a Portuguese brig named Ulysses. In 1839 the ship carried 556 African slaves bound for the Americas. The slaves were forcibly taken from their homes and shipped to the new world from Benin in West Africa. The ship kept them confined as human cargo for the entire transatlantic crossing in only 1,380 square feet of space spread across four rooms in the hold. The girls’ room measured 16 feet by 14 feet and contained 117 captive girls (224 square feet, 1.9 square feet per girl). The boys’ room measured 15 feet by 12 feet and housed 93 young men (180 square feet, 1.9 square feet per boy. The women’s room was 20 feet by 20 feet and imprisoned 107 women (400 square feet, 3.7 square feet per woman). The men’s room was 32 feet by 18 feet and was the cell for 200 men (576 square feet, 2.88 square feet per man). The journey across the Atlantic from Africa to the Americas, known as the Middle Passage, generally took 6 to 8 weeks (42 to 56 days). Ingraham notes that the Ulysses passengers were held captive in these inhuman conditions for 50 days until they were rescued.

The Ulysses was captured by the British schooner of war, Skipjack, while en route to Spanish protection in Cuba. The British brought the Ulysses to harbor in Jamaica, where the slaves were freed from the living hell of their captivity and a grim future of bondage.

Ingraham toured the ship and recorded the horror of his life-changing findings in a journal entry on Christmas day of 1839.

“When told that 556 slaves occupied . . . it seemed almost impossible. O where are the sympathies of Christians for the slave, and where are there exertions for liberation? O it seems as if the church were asleep and Satan has the world following him . . . As I contemplate the awful suffering that these poor creatures must have endured during a passage of 50 days from the coast of Africa, my soul is in distress & I feel to exclaim, “How long O Lord? How long shall these poor creatures be taken from their homes and made to endure so much for the avarice of men? O who can measure the guilt or sound the iniquity of this nefarious traffic and its twin sister Slavery? O that I may pray more often and with more faith for the oppressed.”

Of the original 556 captives onboard the Ulysses, 23 died during the journey crossing the Atlantic.

This 100 + page hand-written personal journal, which recorded Ingraham’s eyewitness encounter with the evils of the slave trade, understandably was preserved at a college founded to train Christian leaders with abolitionist sentiments and by the college president who admired the witness of a former student who embodied the spirit of the anti-slavery movement. In his brief missionary experience, Ingraham established schools and churches for emancipated slaves in Jamaica, eventually known as the “Oberlin School.” His journal is described as “a rich theological text, superbly narrating the 19th-century evangelical approach to social reform.”[1]

No one knows when David Ingraham’s journal was placed in storage in an unmarked box at the back of a closet at Adrian College until the Adrian College archivist rediscovered it in 2015. It had been 176 years since Ingraham had first recorded his thoughts and 156 years since Adrian College was founded. Since the journal was unsigned, was older than the college where it was discovered, and also contained anti-slavery sentiments known to be important to the school’s founding principles, the Adrian archivist, Noelle Keller, who recognized the value of the book, asked for help in learning more about the journal and its origins from the Rev. Dr. Christopher Momany.

In 2015, Momany, a United Methodist clergy and published author, had been Adrian College chaplain since 1996 and was known as one of Adrian’s leading abolitionist scholars. Momany credits his interest in abolitionist studies to important early life experience growing up in the Benton Harbor – St. Joseph, MI communities. He sees his study of the past as being in harmony with his passion for cultivating better race relations in the present. Momany still admires his African-American fourth-grade teacher in Benton Harbor, Geneva Isom, for teaching him lasting lessons in diversity, respect, and compassion for others. He is also grateful for his early learning as a student growing up in the multi-racial Benton Harbor schools while also experiencing the white privilege of graduating from neighboring St. Joseph High School.

Momany learned early lessons in faith at his home church, Peace Temple United Methodist Church in Benton Harbor. He is a proud graduate of Adrian College. He received his Master of Divinity Degree from Princeton Theological Seminary and his Doctor of Ministry degree from Drew Theological School in Madison, NJ.

Momany is also active in Historians Against Slavery, a group of professionals which brings context and scholarship to the fight against human trafficking. Today it is estimated that 27 million people are held as slaves throughout the world. He has also served in leadership among the National Council of Churches. Between 2012 and 2020, he was a member of the writing team that crafted an updated version of the United Methodist Social Principles guidelines for almost 13 million Christians.

Momany shared how the study of Ingraham’s journal has inspired the creation of a multi-racial, multi-cultural team of interested abolitionist scholars. The team wants to explore how abolitionist experiences from the 19th century can inform our understanding and help us with 21st-century racial justice issues. When discussing this project, Momany is particularly grateful for the support he has received from academic team members studying the journal, which is calling itself the Dialogue on Race and Faith from the 19th to the 21st Centuries, or DRF.

He credits help for the project given by colleagues at Seattle Pacific University who secured important grant funding. Momany also is grateful for the encouragement from friends and colleagues at Adrian College, and the enthusiastic interest and support from members of his congregation First United Methodist Church in Dowagiac, MI, where he has served as pastor since July of 2019.

In the six years since his first encounter with Ingraham’s journal, Momany has been busy with significant life transitions[2] while he has continued to help assemble the DRF national team of scholars. Dr. Joy Moore, another member of the Michigan Conference and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Academic Dean, and Professor of Biblical Preaching at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, MN, is also a valued member of the DRF team. The DRF is funded by the Murdock Charitable Trust, the Maclellan Foundation, and Seattle Pacific University.

This Dialogue on Race and Faith team,[3] in addition to studying David Stedman Ingraham’s journal, is traveling together to sites of importance from the 19th-century anti-slavery movement. They are sharing learnings on how issues of faith and race among abolitionists in the 19th century may provide useable history for addressing the struggle for racial justice today.

In their statement of purpose, the DRF Project notes: “During these days, when the history of American Christianity is castigated (often rightly, but sometimes in caricature) for its complicity in racial injustice, is there a way to raise up concrete examples of faithfulness? Are there lessons to be learned as we continue to advance this work?”

This group of scholars met together for five days in early August to tour Oberlin and Cincinnati, OH, important to David Ingraham, the abolitionist movement, and the Underground Railroad. An eight-day trip to Benin in West Africa, planned for December, will revisit sites connected with the slave trade. Benin was once known as “the slave coast” and was the source of much of the slave trade in America. In Benin, the DRF team will hear from scholars about human trafficking in Africa and what they have learned about the lives of abducted and enslaved persons.

In addition to shared study and scholarship relating to Ingraham’s journal and the abolitionist movement, the team will also be reexamining information about other Oberlin contemporaries of Ingraham, including James Bradley, Hiram Wilson, Nancy Prince, the Langston Brothers, and Charles Finney.

The DRF plans to publish a book on their research tentatively titled, “Once was Lost but Now am Found: How the discovery of a 200 -Year Old Abolitionist Memoirs Inspire Faithful Dialogue and Action for Racial Justice.”

The group is also planning to release a documentary about their study and findings. In addition, members of the group will make presentations on their learnings at academic meetings at the American Academy of Religion, American Society of Church History, Wesleyan Theological Society, Society for Pentecostal Studies, and at other churches, Christian universities, and museums in Washington DC (the Museum of the Bible and the African American Museum of History and Culture) as requested.

In their own study, dialogue, and presentations, members of the DRF team also hope to stimulate constructive conversation “about our 21st-century racial issues and how we can learn from the past for the sake of our present and future . . .”[4]

According to the Rev. Dr. Chris Momany, David Stedman Ingraham was so moved by his personal encounter with the evils of the slave ship that he wrote to North American Christians to document the brutality of slavery so that we will teach our children how terrible this is so it will stop.

Ingraham’s journal is a historic eye-witness to the horrors of slavery. If we too value human life, we will also commit to influencing others in the direction of loving one another regardless of race or gender, just as Jesus loves us. David Stedman Ingraham would agree that Jesus’ vision for a more loving world and without the evils of slavery is a treasure worth sharing.

Notes:

[1] Information and quotes about the journal come from the Dialogue on Race and Faith from the 19th to the 21st Centuries (DRF) organizational full project description. The DRF is inspired in part by the study and sharing of the contents of David Ingraham’s journal.

[2] Momany’s life transitions include the death of his first wife, moving from Adrian College to a new appointment as pastor of First UMC in Dowagiac, Michigan, and remarriage.

[3] DRF Team members include Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander, William Seymour Foundation; Ms. Tiona Cage, MSW, Portland Seminary/George Fox University; Dr. Esther Chung-Kim, Claremont McKenna College; Dr. David P. Daniels III, McCormick Seminary; Dr. Segbegnon Mathieu Gnonhossou, Seattle Pacific University; Dr. Diane Leclerc, Northwest Nazarene University; Dr. A.G. Miller, Oberlin College; Dr. Christopher Momany, Dowagiac United Methodist Church; Dr. Joy J. Moore, Luther Seminary; Dr. Stephen Newby, Seattle Pacific University; Dr. R. Matthew Sigler, Seattle Pacific University; Dr. Douglas M. Strong, Seattle Pacific University; Consultants: Dr. A.G. Miller, Carol Lasser, and Gary Kornblith, Oberlin College; several scholars of the transatlantic slave trade in Benin; Ms. Lyssa-Ann Clarke, historian, Oberlin School, Jamaica. Administrative Coordinator: Erin Morrow.

[4] Quote from the Dialogue on Race and Faith from the 19th to the 21st Centuries (DRF) organizational full project description.

Last Updated on October 30, 2023