Joseph Yoo digs into his Anglican roots and discovers how ancient prayers and creeds have a powerful effect on the present.

JOSEPH YOO

Rethink Church

For most of my career as a professional Christian (a flippant way of saying “clergy”), I’ve resisted a liturgical form of worship. I could never articulate a reason why I resisted liturgy. It was simply something I never really experienced. The Korean churches I grew up with were more evangelical and contemporary in worship styles.

When I began to design worship services, I was more focused on the “experience” aspect of worship than any other aspect: let’s make sure people feel the presence of God; let’s move people with the music; let’s set the “mood” to holy.

Looking back, I realize how I may have unintentionally led people into a consumer and self-centered style of worship. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying “contemporary” styles of worship enable the consumerism that plagues our church. I prefer a contemporary style of worship. My mistake was putting all of our eggs in the “personal experience” basket and nothing else. It was about making sure you feel good with Jesus.

The Depth and Breadth of Tradition

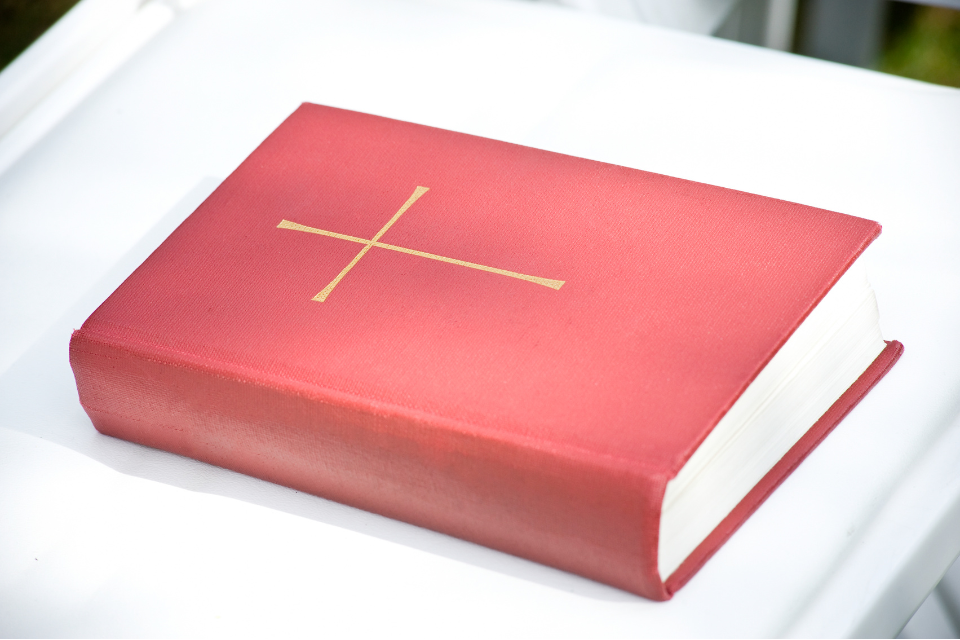

Recently, I’ve been lured to explore our Anglican roots. My current church uses Rite II from the Book of Common Prayer (albeit, loosely) blending in both hymns and contemporary Christian praise songs for music.

There is a wideness to our worship now, I feel. Every Sunday, we say prayers along with all those with Anglican roots throughout the world. We read and hear the same scripture passages with all the churches that use the Revised Common Lectionary. It’s no longer about just me. It’s no longer about just us in the room. We join with the world reciting the same prayers and the same creed.

Then there’s a deepness to our worship that I’ve never experienced before. Some of the prayers we recite on Sundays are centuries old. These prayers of the liturgy use “we/our/us” instead of “I/me/my”. Together, we recite the words of the Nicene Creed that our ancestors have recited since the 4th century.

In this way, every Sunday serves as a reminder that there is more to this world; more to the faith; more to the worship than just me and the people I share the space with.

Maybe it’s just me, but I need constant reminders that it’s never about just me—nor is it ever about me, period.

I’m called to be in community with other people. I stand on the shoulders of people who have gone before me.

I previously always balked at tradition, woefully using Mark 7:8 out of context: You ignore God’s commandment while holding on to rules created by humans and handed down to you. To be fair, some of our local traditions do hold up to this with things like, “we can’t take out those fake flowers from the sanctuary because it’s been there since Majorie Ann was here, although she’s been gone for the past 35 years.”

But my faith journey has led me to reassess many things—mainly to look beyond me and us.

Hearing Voices from the Past

I grew up in a church where all I needed was the Bible and my prayers, further leading me into isolation from the world God so loved and the world I’m called to serve. Be wary of anyone else who sells books or teaches outside of this church because they may be a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Had I stuck to that lane, I would’ve never read people like Richard Rohr whose book Jesus’ Plan for the New World made me reconstruct what it means to be a disciple of Christ. He challenged me to think: am I building God’s kingdom or am I building my own? For me to truly pray “thy kingdom come” in the Lord’s Prayer, I must also pray, “my kingdom go.”

Had I just read the Bible and trusted my pastor alone, I would’ve never stumbled upon Willie Jennings and his commentary on Acts (Acts: A Theological Commentary on the Bible) where the question Dr. Jennings asks (Where is the Spirit leading us and into whose lives?) has haunted me and challenged me ever since I read it. I would’ve never discovered Fr. Gregory Boyle, whose book Tattoos on the Heart showed me what it means to be a community with the neighborhood you serve and what it actually looks like when we follow the Holy Spirit into other people’s lives. It’s also a book I recommend to those planting a church.

I definitely would’ve never came across Rachel Held Evans, who provided words and affirmation for feeling like there should be more to church than what was in front of us.

I would’ve never read Henri Nouwen from whom I learned to let go of the guilt of “not praying the right way” and instead “waste time with God”. (I also believe every pastor should read In the Name of Jesus at the minimum three times during their career.) “Wasting” time with God led me to contemplative prayer which led me to discover breath prayers that I now practice on a regular basis.

What I’m (re)learning the most in this season of my career is to continue to resist wearing blinders and to resist being pigeon-holed and retreating further into my small bubble.

Instead, I’ve begun to understand that to embrace God’s narrative in my life—in our lives—is both wide and deep. I am where I am due to the courageous trailblazing people of faith who’ve gone before me. And from the phrase I’ve learned from Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Ubuntu: I am because you are.

Last Updated on August 3, 2022