Bishop Kenneth Carter revisits Jesus’ parable with America’s health care in mind.

BISHOP KENNETH CARTER

Florida Conference

The first rule of thumb in ministerial etiquette is “do not mix religion and politics”. Of course, people do like it if your politics match their politics, but, of course, people disagree about politics. I am going to mix religion and politics, but I hope to avoid partisan politics. At the same time, I think the subject — health care in America –– is too important for us as Christians to sit on the sidelines.

The first rule of thumb in ministerial etiquette is “do not mix religion and politics”. Of course, people do like it if your politics match their politics, but, of course, people disagree about politics. I am going to mix religion and politics, but I hope to avoid partisan politics. At the same time, I think the subject — health care in America –– is too important for us as Christians to sit on the sidelines.

So let’s get started. Since making the decision to preach about health care, but even prior, I would receive the occasional e-mail suggesting that government should get out of health care. I have come to think about health care from the opposite direction. The church should be getting into health care. This flows from our recovery of the healing ministry of Christ, and the root meaning of our word salvation; as Joel Green of Fuller Seminary notes, “scripture as a whole presupposes the intertwining of salvation and healing.”

The Church got out of health care

Government got into health care because the church got out of it; the church got out of health care because we “spiritualized” salvation, we “disembodied” the soul, we disconnected the mind, body and spirit, and this has had disastrous consequences for the poor, the sick and the creation itself. One of the implications of the incarnation (John 1:14) is that God takes on our mortal flesh; the gift of salvation is, in the language of the Apostle Paul, a “new creation” (2 Corinthians 5:17).

When the church got out of health care (leaving behind a rich tradition of hospitals and hospices formed by the Christian movement), the government took on our work. At this moment we began to lose the connection between our motivation — to continue the healing ministry of Jesus — and our actions — to be his hands in this world. In the name of efficiency and productivity, this work of government was later privatized, and came to be governed by the forces of the economic market. In time the motivation shifted from service to service plus profit, from the common good to the common good plus the creation of wealth. I am not talking about why a physician or a nurse treats a patient. I am talking about how that service is provided and how it is organized.

The way back into the matter, for a Christian, is to reflect on what God wants us to do in this situation. The salvation of God, in the ministry of Jesus, includes preaching, teaching and healing; he ministered to the spirit, the mind and the body. These were the three core activities of Jesus, and the three tasks he gave to his disciples.

What does God want?

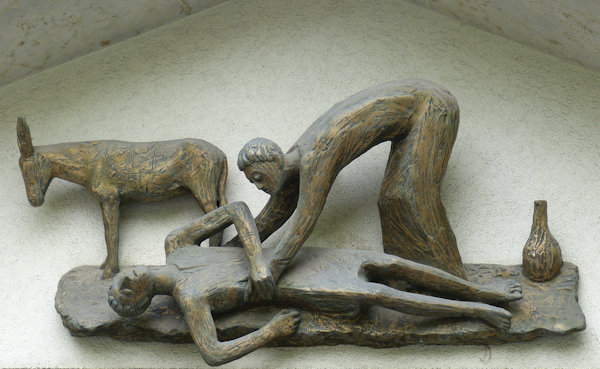

So what does God want us to do? Jesus was asked this question, and he responded in a number of ways, usually by telling stories. God uses stories to get truths into our brains, and this particular story, the parable of the Good Samaritan, is among a small handful of the best known stories in the Bible.

In a culture that is saturated with religious communication, and at a time that our national conversation is obsessed with health care, it is amazing to me that I have heard no one talk about this story of Jesus.

The parable begins with the question of a lawyer, who, like many of us, was not really wanting to learn something new, but making a point. He wanted to know: “what is going to get me into heaven? What is required of me?”

Jesus says. You know the law, you tell me! He responds, Love God and love your neighbor as yourself.

This was also question that the prophets had reflected on, Micah, six centuries earlier, stating it with clarity: the Lord has shown you, and what does the Lord require of you: to do justice, to love mercy, to walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8). Jesus, who stands clearly in the prophetic tradition, would have remembered all of this, he knew the law and the prophets, do you remember Psalm 1, he had meditated on it day and night. Right answer, Jesus says.

But the lawyer could not let it go and so he pushed it, Luke tells us, to “justify himself.” And so he asks, “who is my neighbor?”

Stories of health care

At this point, Jesus responds with what has become a well-known story. If you have been paying attention to the debate about health care, we all have a story, and I asked you to share your stories with me, and you have done that. Many stories have been told lately, when this topic arises: physicians who have less time to treat patients, patients who cannot receive care, or who receive a poor standard of care, or senior adults who may be deemed to be beyond the stage of deserving care, or patients who will not exercise self-care, or corporations who limit care, for the sake of greater profit, government waste. If you watch one network, you are likely to hear a certain story; if you watch another network, you will hear a different story. Each sees a different villain, a different danger, a different hero. Those who tell these stories are not talking to each other; they are talking past each other.

Well, I chose this story, it is a compelling story, but, at a deeper level, what brings us together is not our politics or even our experience of health and disease, it is the One who told this story, and so, I believe, it has a claim on us.

In the parable a man is beaten, and is suffering. A word about suffering and illness: Some suffering and illness can be prevented, and is related to our lifestyle-what we eat, how sedentary we are, whether we get enough rest. Some suffering and illness is unrelated to our behaviors: a friend has a chronic disease, through no fault of her own. Some human suffering and illness is genetic. And some suffering and illness is related to our mortality. We are finite creatures, and some day, maybe sooner, maybe later, we will die. This is for many in our culture a taboo subject, and has been a tool to cause fear and confusion among many of late.

The New Testament teaches us that our bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit, and we are commanded to care for them. Where we abuse them, we and the society suffer the consequences, and more than one physician in our church has said to me that an epidemic is on the way, in our country, related to our self-care. At the same time, we all know many people who are ill through no discernible action, and we make matters worse by implying that they could have done something different and avoided the pain and suffering.

Pass by on the other side

In the parable, there is a suffering person, and the question then becomes, “how do we respond?” Jesus gets to that first by noting how we do not respond, how we avoid a response. We pass by on the other side.

What does it mean, for us, in this moment, to pass by on the other side? One way to pass by on the other side is to say, “it is too expensive, it is too costly.” The paradox is that we already spend more money per capita on spending for health than any other country; however, that help does not always get to the person on the other side—-this is related to the specialties that we fund, and to other factors that are irrelevant to the 46 million who are uninsured, or in growing numbers, under-insured.

Another way to pass by on the other side is to politicize the issue, to fire up the rhetoric and to accuse those who disagree with us of either lacking compassion or being a socialist. I was talking to a friend this week about this sermon and he said, “I am looking forward to seeing how you dance around these issues.” But my sense is that our national debate is not really about health care; it is about politics, and it is a way of passing by on the other side.

Another way to pass by on the other side is to be silent, to despair, to become cynical, but, of course, this is never an option for God’s people. In the parable the Good Samaritan picks up the suffering man, pours oil and wine into the wound, the medicine of the ancient world, binds up the wounds, takes him to an inn, and provides payment for his care, which is somewhat open-ended: whatever it takes, I will return and pay.

Who is a Neighbor?

Back to the question, which Jesus changes: Not who is my neighbor, but which one is the neighbor? For me, this is a simple and yet complex story, and the question of Jesus leads to other questions, including ones of compassion and justice. Mercy is about our command to give. Justice is about another person’s right to receive, and the deeper question is “does the person have a right to health care?”. The parable does not answer this question, focusing more on the Good Samaritan than the man who fell among robbers, more on the question “who is a neighbor” than “who is my neighbor”.

If Christians are to participate meaningfully in the conversation, we will rediscover what is uniquely at stake for us in all of this: the fullness of God’s gift of salvation, which is extended to all people, even the beaten man on the side of the road. A response to the question is going to take people of all faiths and members of both political parties beyond rhetoric to reality. It is going to call forth, not the worst of us, but the best of us, namely justice and mercy, which is, the prophet says, what the Lord requires of us. As in the most effective responses in society to most needs, this will be a public-private partnership.

But I am not speaking, right now, to people of all faiths, or even members of two political parties; I am speaking to Christians. We will be less than Christian toward those who suffer if the political conversation of this summer allows us to pass by on the other side.

Another question: Where will the resources come from to help the neighbor? The answer: they come from us. Now how they get distributed is the complexity of it, and here Christians can, in good conscience, disagree. Do we trust the government to distribute health care? Do we trust an insurance company to distribute health care? Do we trust health professionals themselves to distribute health care? Whichever method of distribution we prefer, each and all of them must be weighed against the biblical concept of justice.

A last question: Where do we locate ourselves in the story? What if you are the person who is suffering? The orientation for most of us is that, if it is someone else, we want care that is good but limited and efficient. If it is for someone we love—-my daughter or sister, your father or grandmother, no expense is too lavish. When it becomes personal, it is different.

For God, it is personal

And this is where the parable leads us, because, for God, it is personal. The neighbor extends farther than we had first thought. Some have a limited definition of neighbor, others have a more expansive definition. Is an aging person the neighbor? Is the unborn the neighbor? Is the immigrant the neighbor? Is the poor person my neighbor? The scriptural answer to each of these questions is yes.

I have wondered lately: can Christians approach this issue of health care in America differently, and I think it is possible. We can offer gratitude to those who have heard the gospel and have moved toward those who suffer, and here I think of health practitioners in our congregations, and how they spend most of their waking moments.

We can repent of the political divisions that have allowed us to pass by on the other side of human suffering.

We can turn toward our brothers and sisters in Christian conversation, in patient listening and measured speaking. And the outcome, with the help of God, may be the channeling of resources toward those who are suffering, and the creation of a world that is more just and merciful.

If we can do this, the parable says, we will live.

~ Note: Bishop Ken Carter preached this sermon on September 6, 2009, on the eve of the passage of the Affordable Health Care Act, when he served at Providence United Methodist Church in Charlotte. He shares it with the General Board of Church and Society as health care in the United States is again in the public discourse.

Last Updated on April 25, 2017