Since February 2017, these four churches in greater Muskegon have been coming together to celebrate historic ties and move forward in faithful witness. They are living their love through action.

CLAYTON HARDIMAN

Michigan Conference Communications

MUSKEGON, MI | February 6, 2019 — Outside the building, there was the usual litany of sounds signaling the beginning of worship at Phillip Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church:

- a quieting of traffic,

- the opening and closing of car doors,

- the sound of familiar human voices, raised in friendly greeting,

- and from inside, the sound of instruments playing and voices singing, making a joyful noise.

The parking lot may have been a little fuller than usual that autumn morning, and maybe there were a few more cars at curbside, but to a pedestrian passerby, it must have sounded like any given Sunday.

Except it wasn’t.

What distinguished this day was the broad spectrum of human diversity inside – white, brown, black and related shades, a kind of rainbow coalition for Christ.

For the past two years, a quartet of Muskegon-area churches have been coming together regularly to share in praise and fellowship and to obliterate racial lines.

In a perfect world, maybe this sort of unity would be routine. But this was not a perfect world. Instead it was a country deeply segmented and crosshatched by lines of race, color and culture, not to mention sharp wounds, long-time rejections, age-old hurts and deep scars.

This is who we have been and who we are – as humans, as Americans, even as Christians.

Sometimes people speak of the Methodist church, as if there were only one. But for more than two centuries, Methodists in the United States have been navigating parallel paths on a divided highway to heaven.

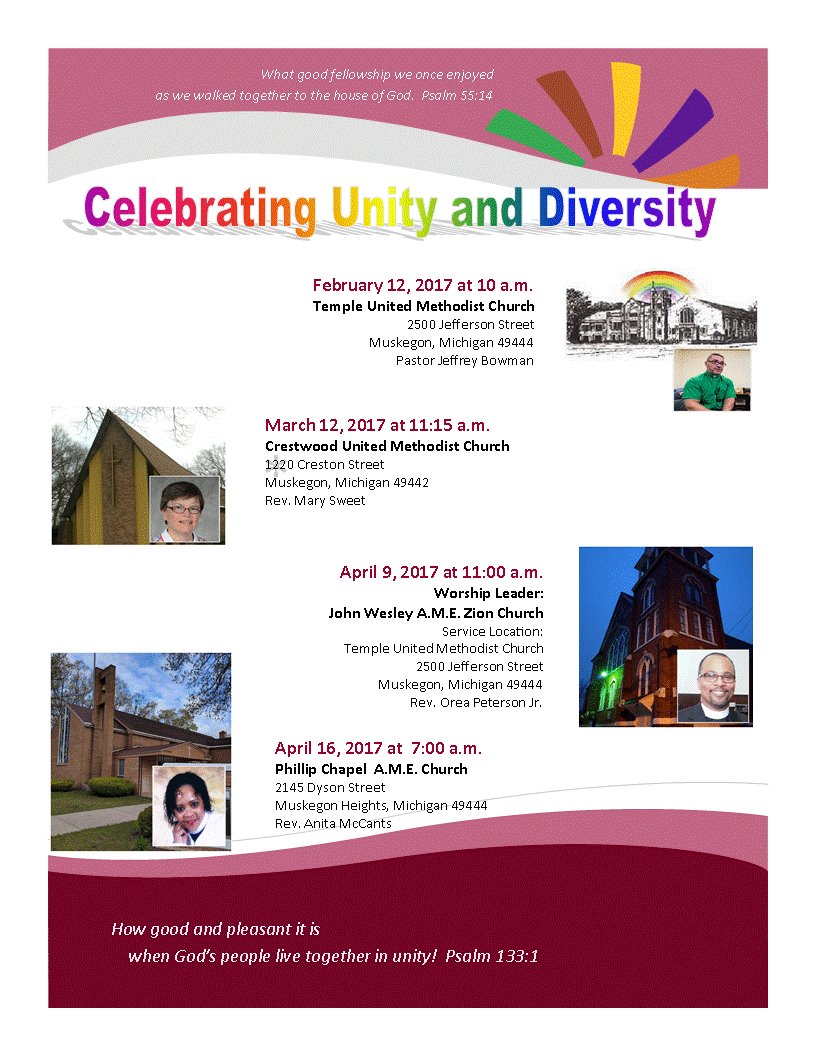

Here in Muskegon and Muskegon Heights, however, in this corner of western Michigan, four Methodist churches have been coming together on a regular basis since February 2017, sharing preaching, music, traditions and styles, enriching each other’s worship experiences and managing in the process to build new relationships.

Two of the churches are majority-white congregations – Crestwood United Methodist Church in Muskegon and Temple UMC in Muskegon Heights. They have been joined by the predominantly black congregations of Muskegon’s John Wesley AME Zion Church and Muskegon Heights’ Phillip Chapel AME Church.

When the pastors embarked on this initiative, they were well aware of what they were up against.

In separate interviews, both the Rev. Anita McCants and the Rev. Orea H. Peterson Jr. – pastors of Phillip Chapel AME Church and John Wesley AME Zion Church, respectively – characterized Sunday morning worship as “the most segregated hour in America.”

It is a much quoted description, often attributed to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose life was ended by an assassin’s bullet more than half a century ago.

But as long ago as that may seem, it is a deceptively short period when compared to the centuries-old rift that has parted black and white Methodists in America.

And yet when the Rev. Jeff Bowman, pastor of Temple UMC, approached the AME and AME Zion congregations with the idea of sharing worship, both were amenable to the idea. So was Crestwood UMC, at that time pastored by the Rev. Mary Sweet.

“We knew there was going to be some push back,” Peterson said. “And we heard it. But the more we did it, the more we saw people begin to fall in love with each other.”

There is a historical context behind this rift between God’s people. It wasn’t prompted by political or doctrinal concerns. Rather, it was boldly, bluntly, nakedly dictated by rejection and race.

The African Methodist Episcopal and African Methodist Episcopal Zion churches sprouted from parallel experiences of discrimination and division – the AME Church in Philadelphia and the AME Zion Church in New York City.

In John Street Methodist Church in New York, worship was conducted according to strict rules of segregation. While white worshipers sat in the main part of the sanctuary, black worshipers watched from the rear of the balcony, almost as if they were spectators. They were served communion only after white worshipers, if they were served at all. Black children were baptized after white children as well. On one landmark occasion, an indignant white minister refused to baptize a black child under the name the child’s mother had chosen – George Washington. The minister chose the name Julius Caesar instead.

At St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, black worshipers were undergoing a mirror image of those experiences. White worshipers distanced themselves from black worshipers. On one occasion, a black worshiper who had begun to pray was interrupted when a white trustee tried to pull him forcibly from his knees.

[youtube v=”xPNfjLqsl5o”]

In Philadelphia, black Methodists left the church. They officially formed the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1816. In New York, black Methodists officially formed an organization that became the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1821. They were the first denominations in the West to be formed on racial grounds rather than political or theological ones.

These were not acts of desperation. Both churches took on prominent roles of leadership in the black community and the nation. Both claimed roles first in the fight against slavery and then the battle for civil rights. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church became known informally as “Freedom Church.”

Both McCants and Peterson say they feel a personal sense of responsibility to continue their denominations’ traditions of integrity and leadership. But they say they also feel bound to pursue the goals of their ministry, which include the gospel, love and service.

McCants quoted the AME Church motto: “God our Father, Christ Our Redeemer, the Holy Ghost our comforter, and man our brother.”

She heard echoes of that motto in the telephone call she received from Bowman after the presidential election in 2016. “He said, ‘Sister, there is nothing but division, division, division,’” she recalled. “‘We have to do something to show we are united in Christ.’”

No one knew how far reaching the initiative would be. Initially organizers envisioned a monthly service that each congregation would host on a rotating basis. It has gone much farther than that.

It has transformed and strengthened relationships, both among individuals and congregations.

Bowman, a white man who grew up in Lansing, and Peterson, an African-American who was born and raised in Flint, have dispensed with formal titles. They now call each other brother.

They credit each other with going far beyond talking the talk. Each says the other has shown love through action.

After Bowman’s mother died, he said, he was deeply moved when Peterson called him in Ohio and texted his support. In Lansing, where the funeral was held, Peterson made a personal appearance.

And when John Wesley AME Zion Church’s building was beset with roof and boiler troubles, the congregation began meeting in a private home. Bowman made it clear that the AME Zion congregation was welcome to share Temple UMC’s facilities. Since autumn, the churches have shared the Temple building in Muskegon Heights, with one service following hard on the heels of the other.

“We really had no choice,” Bowman said. “Is there really a choice? It belongs to you as much as to the people of Temple. Somebody give me one excuse why this shouldn’t happen.”

In one of their few brotherly spats, Peterson has insisted on reimbursing Temple for use of the building. Bowman has argued that reimbursement isn’t necessary.

Since the unity and diversity services have begun, there have been changes. Crestwood UMC received new pastoral leadership; the Rev. Mary Sweet moved and now the Rev. Jennifer Wheeler is an enthusiastic partner in the initiative. Opportunities have opened up for pastors to reach out to each other.

“I believe all of us have grown closer as pastors,” McCants said, but our members have come together, too, across the four churches.

One of the times Bowman experienced that most profoundly was during a foot-washing service at Phillip Chapel AME Church. Bowman said he was moved by the trust people showed in allowing him to wash their feet. “It blew my mind,” he said. “I cried all the way home.”

These are some of the things Bowman never anticipated when he and the other pastors embarked on their unity initiative. McCants said she never believed that two years later the initiative would still be going on.

“I don’t think I anticipated how long it would last,” she said. “I thought we might do it for one or two Sundays.”

Instead, people have found that the experience has paid unexpected dividends.

“The question becomes how do we build tolerance,” Bowman said. “We have to practice it. In tolerance, we find a piece of ourselves.”

It’s not about replacing one’s family but expanding it, McCants said. And how does one expand a family? One way is through marriage.

“We crafted a kind of marriage and found a way to expand our family,” she said.

~ We welcome Clayton Hardiman to the Michigan Communications Team. Before retiring in 2015, Clayton worked four decades as a reporter, editor and columnist for The Muskegon Chronicle.

Last Updated on September 20, 2022