In 1771 Francis Asbury crossed the Atlantic Ocean to take Methodism to the New World. On September 12, people on both sides of the Atlantic commemorated the 250th anniversary of his historic journey.

TIM TANTON

UM News

“Whither am I going? To the New World. What to do? To gain honour? No, if I know my own heart. To get money? No: I am going to live to God, and to bring others so to do.” — Francis Asbury, writing in his journal, Sept. 12, 1771

On Sept. 4, 1771, a young Francis Asbury boarded ship for America, filled with a call to save souls and help lead the nascent Methodist movement in the colonies.

At a conference a few weeks earlier, the 26-year-old preacher had stepped forward in response to a request from John Wesley, co-founder of Methodism, for preachers to go to America. While Asbury wouldn’t be the first Methodist preacher in the New World, he would become the architect for the Methodist Church in America, putting in place an organization that largely continues in The United Methodist Church today, and setting a template for Methodism’s growth in other countries as well.

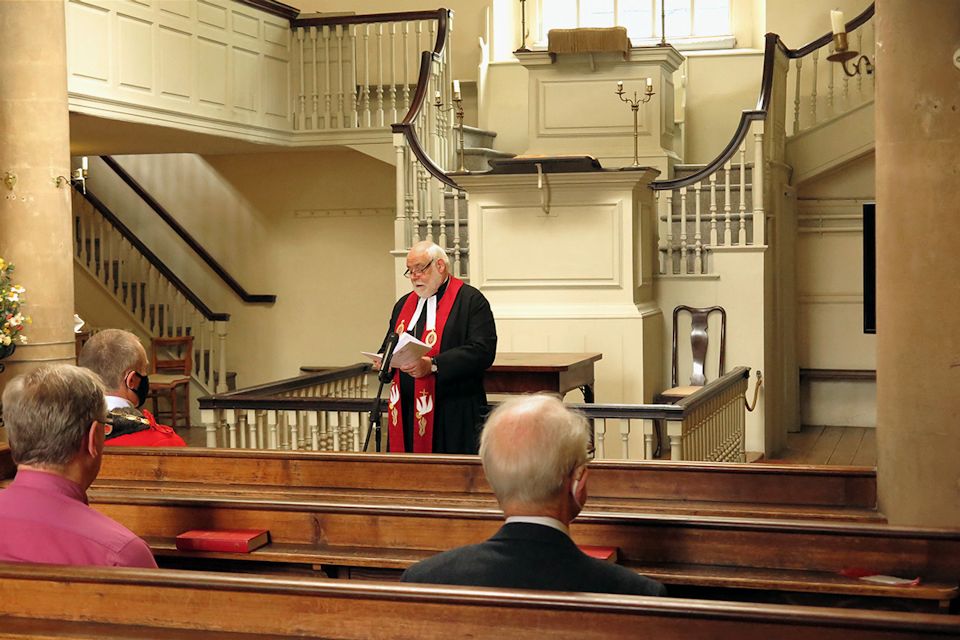

People called Methodist from both sides of the Atlantic commemorated the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s Atlantic crossing with a Sept. 11 online concert and Sept. 12 worship service at John Wesley’s New Room in Bristol. Celebration of “The Asbury Crossing: Responding to Call” will continue with the rollout of resources for churches and individuals, and it will culminate with more special events Oct. 30-31 in Philadelphia. The Methodist Church in Britain and the United Methodist Commission on Archives and History are collaborating on the observances.

“Francis Asbury’s journey across the Atlantic embodies the connection of transatlantic Methodism,” said Ashley Boggan Dreff, top staff executive of the Commission on Archives and History, in an email. “Asbury came to the colonies following a call. He came to sustain and grow Wesley’s Methodist movement, but neither he nor Wesley knew how Methodism would flourish and develop, given the unique challenges of Revolutionary America. This event reminds us of our common roots and the journeys that necessitated our separation.”

During the Sept. 12 service, Barbara Easton, vice-president of the Methodist Church, said she is “an Asbury fan.”

“It is ironic that Francis Asbury is lionized amongst the Americans to whom he went, but he is barely known amongst British Methodists, the people from whom he came,” Easton said.

She recounted Asbury’s humble beginnings in the industrial West Midlands. Introduced by his mother to Methodism, Francis was derided at school “for his religious sensibilities,” Easton said. After leaving school, he became an apprentice metalworker, but “religion took over his life,” she said.

“Most things in life were stacked against him, an apprentice nail maker with little education, and yet he was fired up by the faith that he found, and this gave him an energy which nothing could stop,” she said. “He didn’t have a lot of learning, but he studied to get the education he needed. At a time when people didn’t travel far, he went round and round the extensive preaching circuits of the growing and challenging towns, encouraging people to find a transformative faith like he had found.

“He was said to be an extraordinary preacher,” she said. “He didn’t have a lot of confidence and he didn’t always have good health, but he didn’t let that define him or what he could do for the church. He put up his hand and he said, ‘Here am I, send me.’”

Easton said she hadn’t explored much about what happened to Asbury after he left England, having been more interested in how he had served the church in her region. “But I do know he was a humble man who resisted having his portrait painted because it’s not about him, it’s about God. ‘The Lord,’ he said, ‘covers my weakness with his power.’ And that’s why Asbury strikes a chord with me.”

Marking the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s Atlantic crossing is important for British Methodists as well as Americans, said Sarah Hollingdale, heritage officer for the Methodist Church. Though most British Methodists don’t have a clue who Asbury was, his experience in England prepared him for the challenges of the New World. “His time here in England laid the foundation for his time in America.”

Appointed to circuits — groups of churches — that other preachers didn’t want, she said, Asbury experienced verbal and physical attacks, and when he went to America, he was used to dealing with hostility.

Asbury’s story is as inspiring today as it was then, Hollingdale said. It prompts people today to focus on calling: “What is calling and what does it mean? What is God calling us to today?”

She hopes Asbury inspires people to reflect on calling in their own lives.

“He wouldn’t have cared if they remembered his name or not, but he would have cared that they were inspired by his story.”

The Rev. Novette Headley, a trustee of the New Room and superintendent minister of the Bristol & South Gloucestershire Circuit, said Asbury’s crossing was “pivotal, really, for the Methodist Church.”

Wesley had said the world was his parish, but he couldn’t do all the work alone. “But through his experience and inspiration … he … provided the avenue for Francis Asbury to respond to God’s call to travel and go to America.”

The Holy Spirit brings people together to do God’s work, she said.

The New Room was a natural setting for the anniversary service. Built in 1739, it is the oldest Methodist building in the world. “The sense of Wesley is almost palpable here,” Easton said.

It was in this space, with its wooden floors and austere pews — and under the same clock given by Wesley to keep preachers on time with their sermons — that Asbury stepped forward to answer Wesley’s call. Hardly a month later, Asbury was setting sail from the nearby port village of Pill, with nothing to sleep on but two blankets for 53 nights, according to biographer L.C. Rudolph.

He maintained correspondence with his parents through the years, but despite his mother’s pleas, he never returned to England, writing in 1797 that leaving America would “break my heart.”

“Asbury was so singularly focused” on mission and the spread of the Gospel, Hollingdale said. Brothers John and Charles Wesley had families and friends, but Asbury never took a break. “Asbury was 24/7, and you wouldn’t recommend that for ministers today.”

He stayed constantly on the move, circulating throughout the expanding United States, preaching daily, directing and encouraging his preachers, and organizing the church. He is believed to have traveled more than 300,000 miles on horseback, crossing tough mountain ranges and pushing through terrain where roads didn’t exist.

He had no home of his own but stayed with families. Nevertheless, biographer Rudolph wrote that Asbury became so well known that his fellow bishop, Thomas Coke, addressed a letter to “The Rev’d Bishop Asbury, North America,” and it was delivered. Coke and Asbury were the first two bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church, which came into being shortly after the American Revolution with the strong growth of Methodism in America.

Asbury preached the gospel across the country, going into the countryside when many preachers preferred to stay in the city, engaging with all people, regardless of their background, Hollingdale said. He encouraged Black preachers and ordained them — “something completely unheard of at the time because Asbury trusted that calling was even more important than convention, that he was doing what God wanted him to do.”

He preached almost until the day he died at age 70, she said.

“When he started out in America, there were just hundreds of Methodists — those who had called for help — but by the time he died, there were hundreds of thousands of Methodists. Such was the impact that he made there,” Hollingdale said.

The celebration of Asbury’s crossing encompasses many different elements.

The resources being provided include content on journaling, which was a practice that Asbury adhered to throughout his ministry. Hollingdale said the church wanted people to have something to take away from the celebration that could impact their daily lives, and two missionaries produced an article and video on journaling. Asbury used to journal to reflect on his faith, and whether times were good or bad, he could look back and see how God had helped him, she said.

The Sept. 11 livestream concert was arranged to reflect “the cultural link that Asbury formed with America,” Hollingdale said.

Magpie22, an Americana band based in Bristol, performed a one-hour set that featured original songs as well as “Amazing Grace” and an aptly chosen cover of “A Horse With No Name.”

Dawn Kelly, singer and songwriter for Magpie22, said she’d never heard of Asbury but began researching him after the New Room contacted her about performing. “I was really captivated by the idea that he’s an unsung British hero,” she said.

It is time for British people to understand Asbury and what he did, “because it was monumental,” she said during the concert.

Would the humble Asbury have approved of the celebration?

“I think he’d have wanted us to focus not on him as a person but on his faith, and on the God that equipped him to do the things that he did,” Hollingdale said during the service.

She cautioned against viewing Asbury as just a historical figure.

“Francis Asbury, whether he lived in 1771 or 2021, would have lived out his faith just as audaciously today as he did then,” she said. “And I think that wherever and whenever he lived, he would have wanted to live to God and whatever that looked like, and I think that’s the challenge for us to take away today.”

~ Information and resources on “The Asbury Crossing: Responding to Call” are available from the United Methodist Commission on Archives and History and the Methodist Church of Britain.

Celebrating Asbury’s Voyage to the Americas 250 Years Ago

Francis Asbury: Responding to Call

Video: Hear extracts from Asbury’s diaries

Listen to The Methodist Podcast on Asbury

Last Updated on December 8, 2023