In celebration of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Dr. Jennifer Hahm and Rev. Andy Lee illuminate some of the cultural values and faith practices that sustain their Korean American families.

JAMES DEATON

Content Editor

“One generation will praise your works to the next one, proclaiming your mighty acts” (Psalm 145:4, CEB).

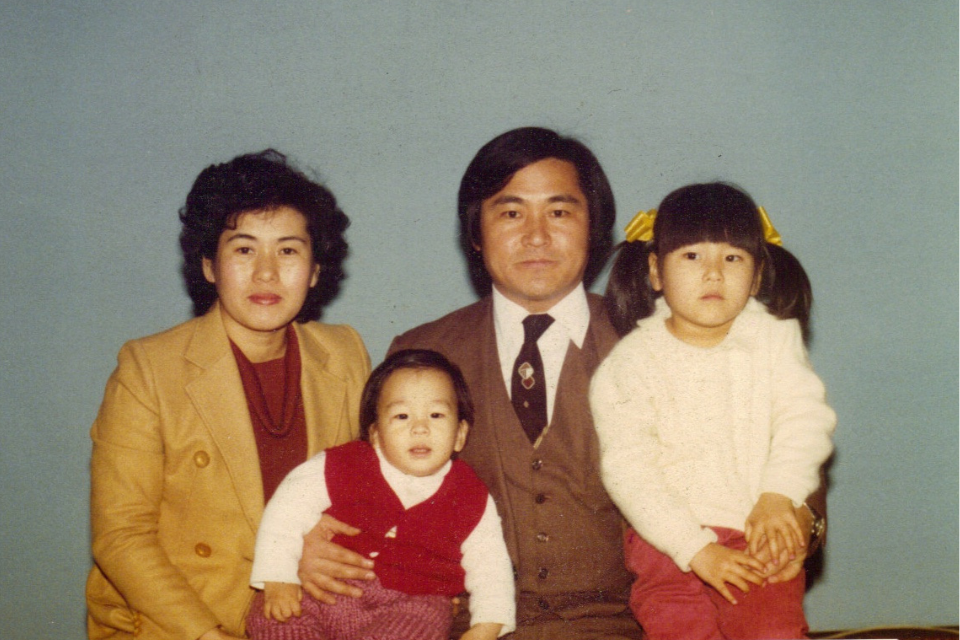

Family plays a crucial role for those growing up in the United States with an immigrant life experience, as cultural and societal influences impact personal development and self-esteem. Parents, caregivers, or other older adults become guides as children witness differences in skin color, language, and traditions and learn to accept themselves.

Second-generation Korean Americans whose parents were born in Korea but moved to the United States and raised their children here feel this tension acutely. These people experience joys and challenges, pain and curiosity. Cultures interact, clash, and meld, yet time and again, people courageously step forward and live into their new identity.

Korean Americans have learned how to navigate the expectations of more than one culture and the reality of being Asian in a predominantly white context. In doing so, they desire authentic spaces where they are seen and valued. They desire to hold on to aspects of their Korean culture, which feeds their souls and grounds them in remembering who they are.

Might the church be one place where they can experience affirmation, where their identity and gifts as Korean Americans are celebrated and integrated into the faith community?

Dr. Jennifer Hahm and Rev. Andy Lee, United Methodists living and serving here in the Michigan Conference, believe the church certainly has a role, but it first starts with family.

Dr. Jennifer Hahm is a licensed psychologist with a private counseling practice who also works as a part-time Ministerial Assessment Specialist for the Michigan Conference, evaluating candidates for pastoral appointments. Her husband, Rev. Paul Hahm, is the lead pastor at Farmington: Orchard UMC. They have one two-year-old daughter, Emilia.

Jennifer says the Korean American experience in the United States is deeply connected to the immigrant experience. Nearly all the adults she knows have parents who immigrated, and third-generation Korean Americans are growing up right now. Her daughter is one of them.

Thinking about her and Paul’s family heritage, Jennifer envisions having conversations with Emilia as she grows older about devoted and conscientious family members and friends. These flesh-and-blood stories will be passed on to Emilia with love.

“She will hear about how her elders embodied courage, adventurousness, persistence, and resiliency in their decisions to leave a country full of familiarity and belonging to set down roots in a place where they hoped for more,” says Jennifer. “One affirmation we are teaching Emilia in her toddler stage is ‘I can do hard things,’ knowing that this statement is a birthright evident through her family tree.”

Jennifer names two specific family members. These two grandparents grew up in a war-affected country and endured hardship, and she wants her daughter to know about them.

“My maternal grandmother,” recounts Jennifer, “grew up during the Japanese occupation of Korea and experienced forced assimilation. One of her brothers was relocated to Japan and was not heard from again. My grandmother practiced Buddhism until she converted to Catholicism as an adult, and I have always known her to be faithful in attending mass, praying the rosary, growing a beautiful vegetable garden, being kind and tender, and nourishing others through healthful food.”

Jennifer will also tell Emilia about her paternal grandfather and how he grew up during the Korean War. She says, “To flee encroaching conflict, he walked over 100 miles with his family traveling southward, finding shelter in deserted homes and buildings. Emilia will learn how he came to be a United Methodist pastor and moved his family, including her father, when he was a year old, to the United States to begin a new chapter of ministry.”

Rev. Andy Lee is the pastor of Commerce UMC. His wife, Grace Baek, is a pediatric nurse practitioner at Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit. Grace is a pastor’s kid. Her father retired from the Michigan Conference a few years ago. Andy and Grace have two daughters: Noelle Hajin, who is six and in kindergarten, and Clara Hayoung, who is three.

Andy grew up in a Korean American family where it was important to be mindful of social hierarchy and mutuality in relationships. He has an older brother who is 13 months older, and Andy was taught to respect and listen to him. The older brother was also taught to care for Andy, ensure he behaved correctly, and include him in games with friends.

The Korean word hyung gets to the heart of this essential familial bond. When Andy was in kindergarten, his mother noticed he had begun calling his older brother by his first name. She set Andy aside and instructed him to refer to him by his honorific title, hyung, which means “older brother.” She emphasized that even if he were in the presence of all their non-Korean friends and had to yell across the schoolyard, he was expected to use the word hyung.

“Calling my brother hyung,” says Andy, “was a constant reminder of who we were, who we were to each other, and how we were expected to treat one another.”

Andy clarifies the title hyung extends beyond siblings. It applies to all older males whose age does not cross to the next generation. He says that many of the same expectations also apply in those relationships. “I have had many good hyungs,” notes Andy, “and I have been a good hyung to others. It all began at home.”

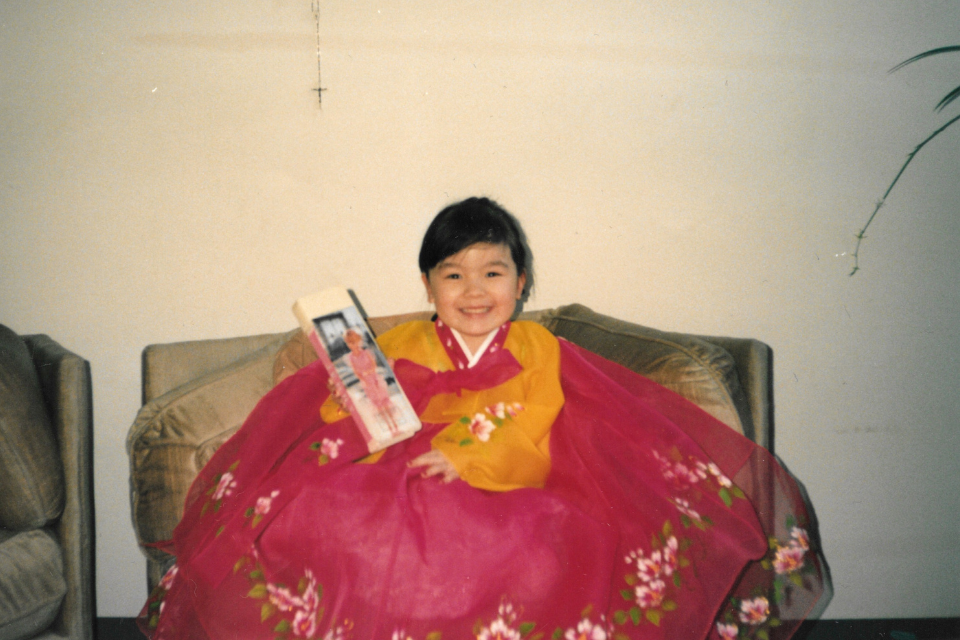

For Jennifer, home is where she and her husband, Paul, are helping to educate their daughter about her Korean cultural heritage. They have taught Emilia her Korean name, Minsoo, and are exposing her to the Korean language. They are teaching her Korean children’s songs, and she has toy blocks and children’s books in Korean. “We also incorporate meals with Korean foods,” adds Jennifer, “and talk about traditional Korean celebrations such as Seollal, the lunar new year, and Chuseok, a mid-autumn harvest festival.”

To provide additional educational opportunities and affirmations in a Korean cultural environment, Jennifer and Paul hope to send Emilia to Saejong School when she is old enough and have her attend a school district with racial and ethnic diversity. Jennifer attended Saejong, a Saturday program for elementary school children and middle schoolers that focuses on teaching Korean culture and history, and she found tremendous value in that experience.

“I am very grateful,” explains Jennifer, “to have had the opportunity to learn more about my ethnic identity and to have had a space that was not predominately white. It allowed me to regularly experience not feeling like a minority. However, I also benefited from attending a school district with a lot of diversity.” Jennifer grew up in Troy, which has a significant Korean population compared to the rest of Michigan.

Andy says that the best way he’s found to honor his Korean American cultural identity and history is to live it out. He and his wife do this at home since there are limited opportunities nearby. Where his family lives now, there isn’t an abundance of Korean language classes or heritage programs, and their preferred Korean grocery store is 45 minutes away.

Like Jennifer and Paul, Andy and Grace make Korean foods at home and incorporate Korean language in everyday interactions. “For our kids’ lunch,” says Andy, “we pack Korean meals, and recently, my wife has recruited our eldest to stuff Korean dumplings, or mandoo. For entertainment, we watch Korean dramas, Korean reality TV shows, and Korean cartoons. Netflix seems to be packed with them now.”

These practices are valuable for Andy, but he longs for a community where these cultural practices can blossom and grow naturally among other Korean Americans. “While my wife and I,” explains Andy, “make sure to practice Korean traditions and observe major Korean holidays with family members, this simply does not compare to being a part of a larger Korean American community that participates in these traditions organically.”

Korean churches, where Korean is spoken and Korean culture is integrated into church life, can be one place where cultural identity is shaped by community. Andy says, “Ethnic churches play a tremendous role in celebrating and continuing Korean American identity, but as a pastor of a non-Korean church, that option is not available to my family.” Andy currently serves a cross-racial, cross-cultural appointment at Commerce UMC, which is almost exclusively white.

Andy remembers the formation he received growing up in a Korean church, especially regarding values and beliefs. He gives two examples — giving our best to God and having an intentional prayer life.

One value that he cherishes and wishes to emulate and pass on to his daughters is the attitude of giving one’s very best to God. He tells a story of his parents giving him a crisp dollar bill to put in the offering each Sunday. When they didn’t have one readily available, his mother would take an iron and flatten the crinkled bill to ensure he gave his best to God.

Later, as a teen, Andy helped members of his church, Korean First Central UMC in Madison Heights, copy the entire Bible in Korean by hand. He wrote several pages but made a few errors, so he used whiteout and wrote over the mistakes. His parents instructed him to start over. Andy wasn’t happy about it, but his mother’s prodding helped.

Andy remembers, “She asked me to consider the occasions I made my friends or loved ones a birthday card. In those instances, if I made a mistake, would it not be reasonable to start over with a new card? When I told her I would certainly start over, I began to understand better why it was important to rewrite those pages for the Korean Bible.”

“To this day,” asserts Andy, “I want to give God my best. This attitude informs my preaching, continuing education decisions, and life in general. I hope that my children will take the same approach. Whatever they do, may they do it as an act of worship and a sign of love to our God.”

The second formational practice Andy would like to pass on to his daughters is the spiritual discipline of prayer. Growing up, his parents would take him and his brother to church for early morning prayer and devotions. With dozens of others, they prayed aloud in bold cries to God in tongsung kido. Verbalizing their global and personal concerns was a healthy model for Andy to experience and learn powerful, honest prayer to God.

“Over time,” says Andy, “I began to see prayer as a necessity. It was like a miracle drug — a real game-changer. Most of the people in attendance, including my parents, regularly worked 70-hour weeks. Many owned small businesses, such as dry cleaners or beauty supply stores. Sitting in my pew, I was tired from waking up so early, but everyone else must have been even more exhausted. When we concluded, we felt God’s presence. We left strengthened to engage the complexity of our lives, to endure unresolved tensions, and to work long hours.”

In his current church context, Andy does not practice tongsung kido or early morning prayers, but he pushes his congregants to pray boldly, dream big, and expand their vision to participate in hard things. “We can indeed make tremendous contributions to God’s kingdom,” says Andy, “and if we are in a place where we do not believe this to be so, we must go to God in prayer.”

Andy also wants his daughters to have a strong prayer life and tap into this amazing channel of grace. “Unfortunately, I have already observed instances where they have been excluded, overlooked, and ignored based on their appearance. I can foresee my daughters internalizing a negative self-image as a result. I have struggled with this at various times in my life. So, every day, we pray together. My youngest is quite comfortable with prayer, while her older sister needs more encouragement. I am happy to encourage them, just as I was encouraged by my parents. In the next several years, I may be dragging my children out of bed at 5 am during spring break so we can sit in a pew at grandma’s church to engage in tongsung kido.”

Jennifer also speaks to the cultural and spiritual value of ethnic churches. She grew up attending Troy: Korean UMC (now Korean Methodist Church of Detroit). She explains, “You did not have to explain or carry the weight of how salient cultural differences felt. It took a toll to be expected to know both cultures — you were born here, so you should know what it is to be American, but you must also know what it is to be Korean to maintain family and ethnic community connections. And from that, the Korean American experience emerges.”

Troy: Korean UMC was a space centered around Korean and Korean American culture and one more place to have a sense of belonging. “You did not have to explain,” says Jennifer, “why your parents had an accent when speaking English or why you often had to serve as a translator or interpreter when it came to school forms or communication with teachers, why you ate different foods than typical American cuisine, why there was a lot of focus on getting good grades at school, or why you did not have longstanding family traditions for Thanksgiving or Christmas, including why it was not that unusual as the oldest sibling to have been the Easter bunny or Santa Claus for your younger siblings and never having had someone do it for you.”

The Korean church, says Jennifer, has shown her the importance of having places of refuge and respite from the numerous ways society tries to tell so many people that they do not belong. It has also challenged her to think about how the church can be that place for people of many different identities and circumstances.

“These experiences in the Korean church have shaped me into a parent who wants my child to know that she does not have to comply herself to spaces in which there is pressure to ‘melt away’ differences. In Emilia’s spiritual formation, I want her to know she can work toward finding and creating space that is inclusive, collaborative, and invitational of the many gifts, qualities, and attributes people of different identities, experiences, and circumstances have.”

“I know there will be elements to her identity,” concludes Jennifer, “such as being third-generation Korean American, that I will not have any lived experience with, and I look forward to learning more about that from her in time.”

Last Updated on June 4, 2024