A health care professional challenges the church to see God in those with HIV/AIDS.

ALEX PLUM

Lay delegate, Detroit Conference

As a kid, I looked forward to vacationing on Lake Charlevoix every summer. We would go up north with several families and rent cabins on the south arm of the lake. Together with my dad and his sister, and their high school and family friends, we became for one another an extended family. I am still grateful for my many “extended aunts and uncles” who wiled the time away with me swimming, fishing, jet-skiing, and playing volleyball.

One of my extended “uncles,” Greg, would drive up in his red, classic Chevy convertible. Although tall and thin, what really made him stood out was his pale skin and all the sunscreen he used so he didn’t get burned on the beach. Greg spoke softly and mostly kept to himself, but he was always happy to make time to talk when I would ask him about his car. He usually came after we’d been there a few days, he never stayed long, and he always came alone. And that always made me feel sad for him – that he didn’t have the kind of family I did and that he didn’t look like he “fit-in” the way the rest of us did. A teenager, I remember hearing rumors that he was gay, and, being very insecure at that age, I conflated a lot of fictions in my head about him and his identity. A few years ago, when I learned that he had died of complications from AIDS, I was overcome by guilt. By creating my own version of Greg, I denied him the respect and humanity of acknowledging his authentic self. In a word, I stigmatized him (even silently) because of my own fear, prejudice, and lack of understanding.

Stigma is a nasty thing. In some ways, it’s the real reason that public health practitioners like me are still so far from eradicating the disease. Stigma is every bit as pernicious as the HIV/AIDS and maybe worse. While HIV might infect one person, stigma infects the minds and spirits of that person’s entire support network. In my global health work fighting HIV/AIDS, I have listened to men and women, young and old, as they told stories about their friends who suddenly stopped returning their phone calls and their employers who made work so unpleasant they eventually quit. I’ve heard from youth as young as 14 tell me how their own parents kicked them out because of their HIV status.

Those stories devastated my spirit, and they made me angry. One story stands out for being especially graceless: a young man told me that his church – the very place where God invites us into relationship with Godself and offers us a healing balm – asked him not to come back because his HIV represented a divine retribution for his sins. I will never be able to fully appreciate the depth of this perversion of who and what the Church is called to be.

It should be no surprise, then, that people afflicted by HIV/AIDS keep it a secret. Of the 37 million people all over the world who live with the disease, almost half (a staggering 46%) don’t know they have it. While many lack access to testing and treatment services, others refuse to even learn their status out of fear of being labeled, cast out, and rejected. The United Methodist Church can play a vital role at reversing this trend by prophetically calling out the evil powers of our world and inviting all of God’s creation into healing and saving relationship with God. Heck, the United Methodist Church could simply be a place of Open Doors for all who would seek Jesus.

Being at General Conference, I’m reminded of the potential that our mission field brings to eradicate this scourge. Our fastest growing region in the church, Sub-Saharan Africa, also happens to account for almost 70% of the world’s new HIV infections. I’m inspired by the cross-contextual relationships happening here that promise future partnerships to expand access to treatment and support for all people affected by HIV/AIDS. Here in the US, the disease burden of HIV/AIDS disproportionately afflicts Black men who have sex with men. To reach this group, our church has to be willing to face and deconstruct the stigmas we have created and reinforced that prevent the message of God’s saving love from reaching this most vulnerable and marginalized population. HIV/AIDS, and the stigma we allow it to breed, must no longer be able to threaten the bodies, minds, and spirits of our brothers and sisters all over the world.

This I believe: the United Methodist Church is called to leverage our infrastructure, our leadership, and our very identity to break stigmas and stop new HIV infections in EVERY ministry setting all over the world. The United Methodist Church must stand up to stigma and proclaim that all people, including those affected by HIV/AIDS, are made in the very image of God and worthy of God’s sacred grace. Until we do this, we claim to be the Church.

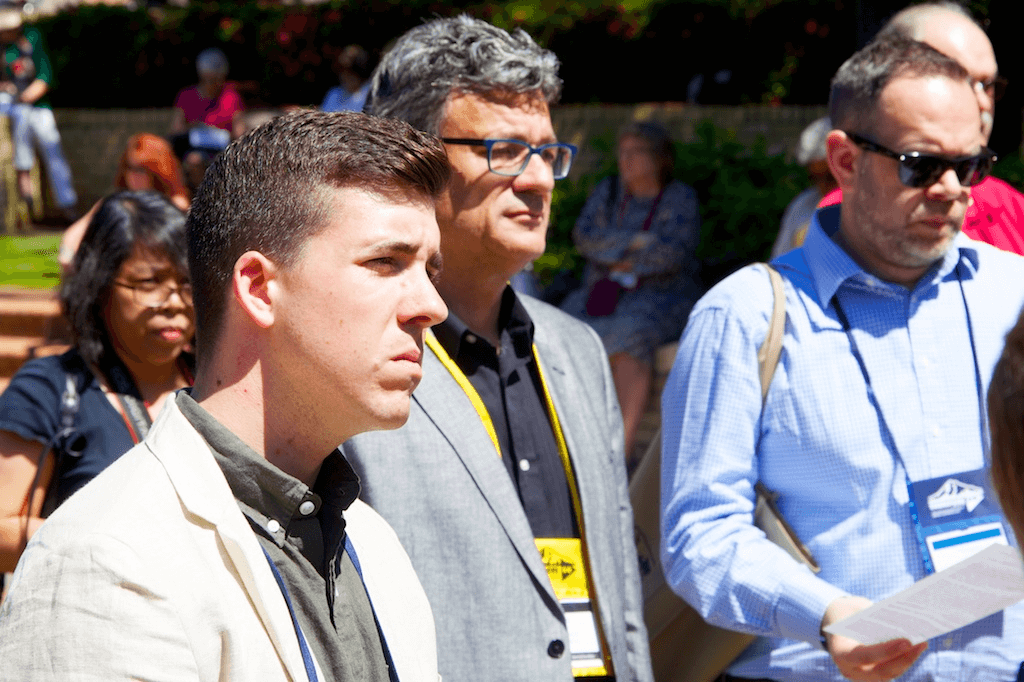

Standing with many other delegates during today’s General Conference AIDS Vigil, I listened to my colleague delegates from the Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone softly say the names of people in their lives they knew who had died. As I lifted up Greg’s name, I asked God to release the stigmas and guilt in all of our hearts. May this prayer, and the countless prayers of the saints from across our connection, help the United Methodist Church to see the face of God on the people affected by HIV/AIDS; those people are all of us.

~Alexander Plum is the Senior Program Coordinator of the Global Health Initiative at Henry Ford Health System. Names used in this article were changed to protect identity.

Last Updated on September 20, 2022