Glenn Wagner reflects on the testimony of his father, who served his family with love, this country as a veteran of the U.S. army, and God through a faithful life of prayer and service.

GLENN M. WAGNER

Michigan Conference Communications

Veterans Day, observed annually on November 11, honors those who have served our country in the military. My dad, an infantryman in the U.S. army during World War II, died at the age of 74 on Veterans Day in 1999.

On this Veterans Day, I remember my dad’s life, his service, and his lasting influence, with hopes that others will also find ways to honor veterans who deserve our profound gratitude for their service.

David Prugh Wagner was born in Chicago, Ill., on January 14, 1925. His dad, Melvin Wagner, was the vaudeville editor and a political cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune. His mother, Mildred, was a homemaker. My dad is survived by his younger sister, Mary Crosset, of Cincinnati, Ohio.

After graduating from Evanston High School in Illinois, Dad enlisted in the army and served in World War II in Europe. In the fall and winter of 1944, Dad fought with other Allied troops against German forces in three violent battles: the Battle for Brest, the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest, and the Battle of the Bulge. Of the 44 men in Dad’s platoon, he was one of only ten who survived the carnage. After thirty days of sleeping outside in subzero temperatures, he suffered from frozen feet and a shrapnel wound. Both conditions required medical treatment in a field hospital. Medics had to cut off Dad’s frozen boots to treat his feet. No size fourteen replacement boots were available on the battlefield, which likely helped spare Dad from further bloody fighting while he recuperated.

After the war, Dad earned a mechanical engineering degree from Purdue University with assistance from the newly passed G.I. Bill of Rights and then returned home to Evanston, Ill., where he met Doris Rhodes, a Northwestern University coed, at a fellowship event held near the campus at Dad’s home congregation, First Methodist Church. They were married in 1951 in Mom’s home church, Van Orsdel Methodist in Havre, Montana.

The Wagners settled in Elmhurst, Ill., because Mom had been hired there as an elementary school teacher and because Elmhurst is situated halfway between where Dad was employed in Elgin and Dad’s hometown of Evanston. Here he was able to offer support for his aging parents. David Wagner was gainfully employed as a mechanical engineer for the Shakeproof division of Illinois Tool Works, designing fasteners primarily for use by the automotive industry to help hold cars together.

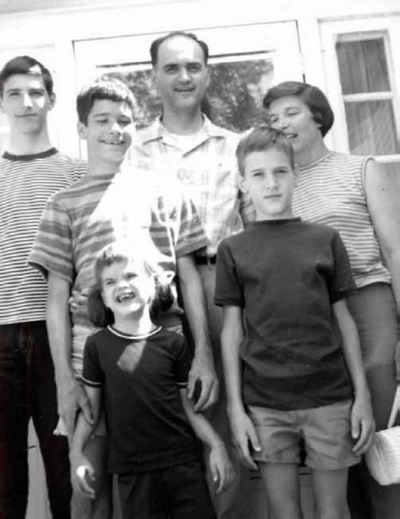

Dad was a positive role model for his family, which initially grew to include my late older brother Doug, me, and my younger brother Richard. Dad was hardworking, compassionate, had a good sense of humor, was a faithful husband, and had an appetite for learning new things. Thanks to Dad’s initiative, we spent our summer vacations traveling and camping as a family across the United States and parts of Europe.

Dad shared his love of athletics with his sons. At 6 feet 6 inches in height, Dad played center for his high school basketball team, and his long reach helped him excel as a member of the Purdue University squash team. He taught us how to compete, be good sports, and play by the rules. He introduced us to the value of groups like Sunday school, Boy Scouts, and the local YMCA. He was a faithful fan at our sporting, school, and church events.

When I accidentally threw a baseball through our kitchen window while playing in our backyard, Dad showed me how to measure for a new pane, took me to the hardware store to purchase the replacement glass, helped me to install and glaze the window, and set up a regimen of yard chores with a salary for my labor so I could pay for the repair. That vital life lesson taught me to play baseball at our school and how to mow the lawn, glaze a window, and weed the garden!

Dad loved to put his engineering skills to work in do-it-yourself projects around the house. As our family grew, Dad recruited my older brother Doug and me to help him remodel our unfinished basement with two additional bedrooms and a bathroom. He and Doug refurbished an old player piano that brought hours of exercise and entertainment into our home.

At First Methodist Church in Elmhurst, Dad was named chair of the building committee tasked with a significant construction effort to add fellowship and educational space to the original church building. He was also active in a Sunday school class that took a public stand for fair housing and helped to move the first African American family into Elmhurst. That same group of faith friends also assisted in helping to resettle refugee families from Vietnam, Cuba, and Eastern Europe.

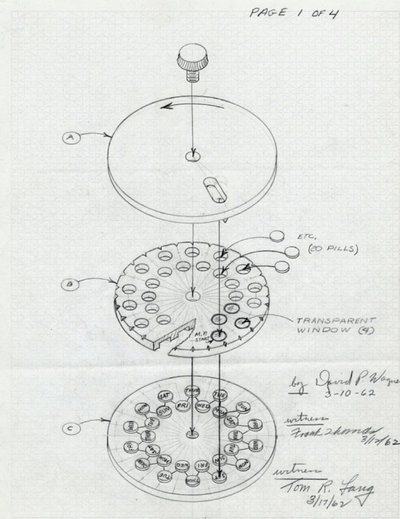

When Mom became pregnant again for the fourth time after my pet cat knocked her carefully arranged birth control pills off the top of her dresser and onto the floor in disarray, Dad went to his workshop at Mom’s request and devised a solution. He invented the first calendar birth control pill box in the United States that is now part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

On Wednesday, November 14, 1961, my sister Jane was born at Elmhurst Memorial Hospital. Jane was born extensively brain damaged, and a bad case of infant pneumonia further complicated her condition. Jane was quickly moved to intensive care. Our family physician didn’t expect Jane to survive her first night of life.

Dad came home from the hospital around 9:00 pm to relieve our sitter, a retired schoolteacher who had been trying hard to manage three active Wagner boys: Doug, 11; Glenn, 9; and Richard, 5, while Dad had been with Mom for the delivery. Dad was somber. He broke the news to us that we had a sister and reported Jane’s precarious medical condition.

Dad then suggested that we spend some time lifting Jane in prayer. The Wagner men joined hands, standing in a circle around our kitchen table. Dad led the prayer asking for God’s help with Jane’s survival.

Prayer for me prior to that moment had been habitual. I mouthed prayers like the Lord’s Prayer from memory at church but didn’t really know what big words like temptation, trespasses, and forgiveness meant. Prayer at home was usually an exercise to get to the meal: simple, short, sweet. “Thank you, God, for this food. Amen. Let’s eat!” Prior to Jane’s birth, I never had any sense of why prayer was important or any awareness of the God who was the focus of our prayer.

The prayer on the day of Jane’s birth was life-shaping for me. As Dad spoke, I was aware that these words being offered to God came from a different place than the “quick, let’s get this over with” prayers of my past. I felt surrounded by a larger presence in the room.

The next morning, the doctor reported, “I don’t know what happened last night, but your little girl has rallied. It looks now like she’s going to make it, but don’t get your hopes up. Jane’s brain damage is so extensive that she may never be able to get out of bed. Her entire life may be spent totally dependent on your care.”

The joy of answered prayer sobered with the looming unknown.

Despite the grim diagnosis, my parents never gave up hope. Heartfelt prayers for Jane continued as part of our family routine.

Following an extended stay in the hospital, we welcomed Jane home and gradually adjusted to her presence. Jane was like any baby; she slept, ate, soiled diapers, and cried when unhappy. But unlike other children, Jane had no muscle control to move around independently. It was far easier to see the reality of the doctor’s grim predictions than God’s unrevealed plans.

Mom and Dad searched for help from people who had experience treating brain-damaged infants and found an experimental program at a children’s hospital in Chicago.

Child-care specialists there knew that in a healthy child, a first developmental step is learning to crawl. Crawling is a prerequisite for walking and talking. Physicians also had learned that the development of a normal child’s brain is most dramatic in the first six years and that stimulating that brain with early opportunities for learning enhances the capacities for development later. Those same doctors worked on the hypothesis that if this early capacity for development was true for healthy children, then perhaps brain-damaged children could be helped in their growth, too, through a program called “patterning.”

By moving Jane’s body for her in a crawling motion, doctors hoped that new pathways would be patterned into Jane’s developing brain, and she too could learn to crawl and then to walk and talk. Our family embraced the patterning program for Jane. Three times a day for five minutes at a time, 365 days a year for seven years, three to five partners gathered around my sister to manipulate her body and perform the patterning physical therapy.

Jane’s inert body was lifted onto a sheet-covered foam pad that lay on top of that same kitchen table where we prayed for Jane. One team member was tasked with rotating Jane’s head from side to side. There were four additional partners, two standing on each side of the table and each asked to move one of Jane’s limbs in a synchronized crawling motion. The exercise never varied.

Because Dad worked and we boys were in school, the patterning team needed additional recruits. Our church family provided most of the extras needed to perform the therapy. Together we learned unforgettably the power, necessity, and beauty of the body of Christ, which gathered daily to affirm that even my sister Jane mattered to God.

Dad took time after he came home from work to read with Jane. When she was old enough, he took Jane to swim therapy classes at the local pool. He made flash cards to teach Jane how to read and do basic math. When Jane was a teenager, Dad helped her learn how to ride on the back of a tandem bicycle.

This formative experience in daily prayer and regular caring for Jane significantly influenced what my brother Richard and I later discerned as our “call from God” to enter the ordained ministry of The United Methodist Church.

I am also thankful for other cherished memories of Dad.

On his retirement from his career at Shakeproof, the manager of another division of Illinois Tool Works wrote Dad a testimonial letter thanking him for his invented fasteners that had led to the creation of the new factory that was employing 200 people.

In his last 10 years of physical decline, Mom and Dad hired a Polish immigrant to help them maintain their life at home. In gratitude for his service and friendship, Dad and Mom sponsored Henry for American citizenship.

Dad died of complications from Parkinson’s Disease on Veterans Day, November 11, 1999. Grief at his death hit me hard. Three days after his death, and 37 years after Dad had gathered his sons around a kitchen table to pray for our sister’s life, his family gathered to celebrate Jane’s birthday. There was a noticeably empty chair at the head of our family table. We were happy for Jane and remembered again God’s grace at work in our lives through Dad.

Jane, who will be 61 this November, remains an important part of our family life. She is employed as a house cleaner and lives in a group home with a house parent as a part of a world-class community for special needs adults in Libertyville, Ill., called Lambs Farm. Jane calls me nightly on her cell phone. She has the remarkable gift of loving others unconditionally. Jane’s life has taught me that life matters, everybody counts, compassion is a powerful force for good, and there is power in prayer and in the body of Christ.

Dad’s memorial service on November 16, 1999, was a fitting tribute to a great man. David P. Wagner, you brought me into the life-altering awareness of the presence of God during your prayer for Jane on the night of her birth 61 years ago. You modeled God’s love as our dad. This Veterans Day is another opportunity to thank God for your great service to your family, your country, and God. I love you, Dad.

Last Updated on November 9, 2022