Retired pastor Glenn Wagner shares important lessons learned through an heirloom player piano about living faithfully with life’s tensions.

GLENN M. WAGNER

Michigan Conference Communications

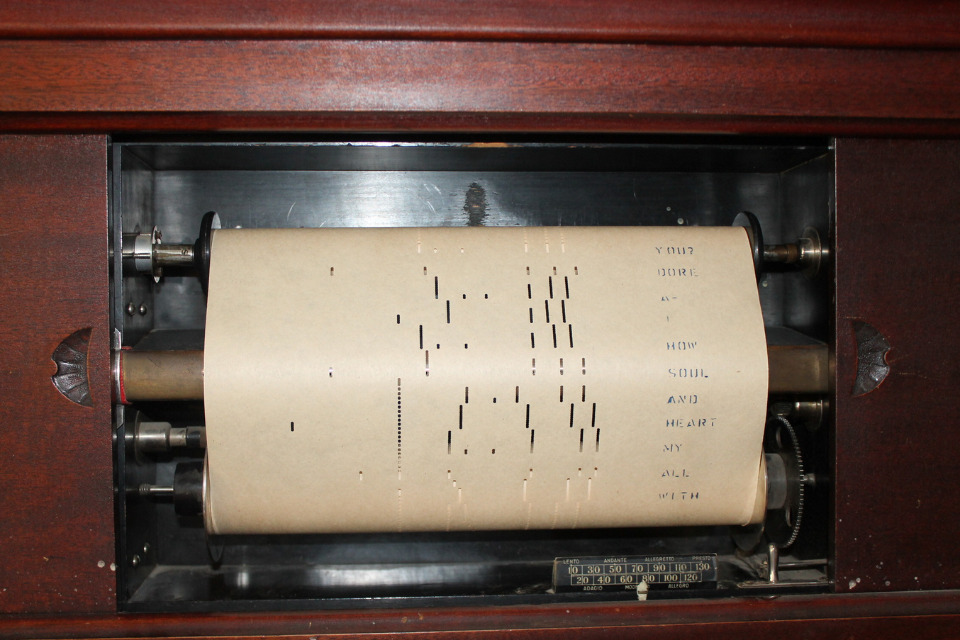

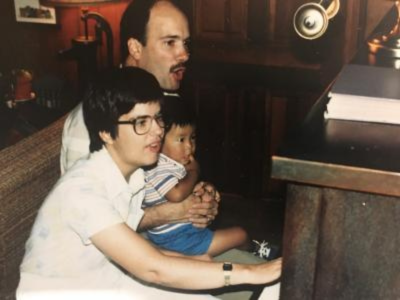

The player piano that graced our family room during most of my growing-up years in Illinois was more than a source of entertainment for family and guests. That piano was a source of treasured memories for my mother, who learned to play it during her childhood in Montana. That same player piano helped my dad and my older brother, Doug, learn new skills when they rehabbed the internal mechanics that allowed it to play rolls of specially perforated paper, which programmed the playing of keys to make quality music just by pumping the piano pedals with one’s feet. The pedals powered the piano’s internal bellows that blew air through the piano rolls and activated the keys. Our special-needs sister, Jane, loved to play her favorite songs on this same piano, like The Stars and Stripes Forever, The Old Rugged Cross, and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. Pumping the pedals provided physical exercise as well as musical enjoyment. Our player piano was also a reminder of significant U.S. and family history that has helped me better understand and live with grace amid many continuing tensions.

The piano came to us in Illinois as part of my mother’s inheritance following the death of her parents and the breakup of her childhood home.

Initially acquired by my maternal grandparents in 1930 during Prohibition, the piano symbolized the real ethical tensions that continue to exist for people who love Jesus and wish to serve him faithfully in a world full of moral dilemmas that resist easy answers.

My maternal grandparents, Jeanne Maris and LeRoy Rhodes, were married in Havre, MT, in June 1918 at the Van Orsdel Methodist Church by Brother Van, the founding pastor. My grandmother was a charter member of the church. At the time of their marriage, Jeanne was a math teacher in the public schools and LeRoy was an attorney.

Jeanne was also the stepdaughter of a Methodist circuit-riding pastor, Rev. Joel Walker. While Walker received a Methodist seminary education at Garrett Biblical Institute in Evanston, IL, my grandmother received her teaching degree at Northwestern University. Methodists began the town, the seminary, and the university in the 1850s as models for Christian community and to develop principled leaders in the Northwest Territory. (Click to read more history.)

Jeanne followed Rev. Walker, her mother, and her brother west to Montana following graduation when Joel was appointed to serve as pastor of the Glasgow Methodist Church. Jeanne eventually found a full-time teaching position in Havre. My grandfather, LeRoy, graduated from Valparaiso Law School in Indiana and followed his farming parents to Montana when they were recipients of a federal land grant program established to bring settlers west to build communities along the vast expanse of the Great Northern Railway.

Grandmother Rhodes was elected president of the Havre chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), part of a national movement founded in 1874 to promote abstinence from alcohol and expanded women’s rights. In 1920, the WCTU was instrumental in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors in the United States. This amendment was repealed by the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933, which granted the rights for the regulation of alcohol to individual states. Abstinence from alcoholic beverages was an important part of my grandmother’s Christian witness.

Following a devastating fire in Havre in 1904, the town rebuilt its main business district below ground. Today, Havre Beneath the Streets is a local tourist attraction that contains displays of Havre’s former underground businesses, including brothels and taverns.

My grandfather, LeRoy Rhodes, supported his family by providing legal services for members of the Havre community. One of his clients had been arrested for smuggling illegal alcohol across the nearby border with Canada during the Prohibition years. The alcohol was intercepted in Havre before it could be shipped east aboard the Great Northern Railway for eventual distribution through gangster Al Capone’s speakeasies in Chicago.

Grandfather was paid for his legal service by the cash-strapped bootlegger with the player piano that had previously offered music in an underground Havre saloon.

Imagine the theological debate on the front stoop when Grandfather brought the piano home. He argued on behalf of the practical matters of feeding his family and providing for legal defense as a matter of common good. Grandmother most certainly countered passionately in defense of holiness and against the known adverse social consequences of drinking to excess, which was also illegal at the time. Could a godly family accept such an instrument that had been used for an unholy purpose? The Rhodes family chose to live with the unresolved tension. The piano came inside their home, but our family always remembered where it came from. Mom learned to play music on that instrument. She did play more church hymns than honky-tonk. The piano roll collection, just like life, offered a wide variety of musical options.

Tension, like that experienced in this personal memory of a player piano, is still very much a part of everyday life. Similar tensions are revealed in the lives of congressional representatives who are pressed by tragedy to decide on proposed gun control legislation following another mass shooting close to home while also representing a district that benefits greatly from profitable gun manufacturing employers who contribute to campaign coffers. Discernable tensions exist in the life and death debates over abortion rights when it is apparent that there are profound exceptions to every rule that resist one-size-fits-all legislation. Environmental activists committed to saving our planet from global warming meet stiff resistance from many whose lives depend on the continuing prosperity of the oil and gas industries. Nuanced wisdom rarely makes for winning campaign slogans or boosts ratings for the TV news.

The recent painful departure of disaffiliating congregations from our United Methodist denomination over issues of inclusion and differing understandings of scripture is another example of life’s tensions.

When I learned to sing, “Jesus loves the little children, all the children of the world,” our elementary Sunday school teacher did not mention that living with love for all is complicated!

The Bible helps us understand there is nothing new in the tensions that exist today between people of faith who regularly face off in real-life debates on consequential issues and frequently believe they are the holders of God’s moral high ground.

Remember the tension between Jacob and Esau over which of the twin brothers deserved the inheritance rights of the family’s firstborn (see Genesis 25–27)? Esau was the firstborn and beloved by his father, Isaac. Jacob was his mother Rebecca’s favorite and had reportedly tricked his brother into ceding his rights to him. The tensions in the family over these matters of inheritance led to Jacob leaving home to begin a new life and start his own family in another country. But the conflict with his brother, Esau, had never been resolved. When Jacob finally began a return journey to his birth home, he learned that his brother was on his way to greet him with an army. Jacob rightly feared a potentially violent encounter with Esau over the festering family inheritance rights. In a dramatic night of wrestling with God prior to an uncertain reunion with his still aggrieved and more powerful older brother, Jacob was permanently crippled by his wrestling and subsequently changed his name from Jacob to “Israel,” which means, “He wrestled with God.” Jacob/Israel’s permanent limp and corresponding name change remind us that a loving God does not free us from wrestling with life’s real tensions. People of faith and twin brothers don’t always agree or get along.

Glimpsing in the rearview mirror at tensions from the past, I am grateful for ancestors who fought battles to end slavery, expand political rights, defeat genocidal Nazis, and guarantee freedom of speech and religion. I am also grateful for a special piano that helped me to learn to sing the songs of faith applied to real life. Music is made when the piano keys strike the strings tuned and held steady in tension.

Last Updated on August 1, 2023