Simon of Cyrene was an African man summoned from the crowd to carry Jesus’ cross to Calvary. The Rev. Henry Masters tells his story.

SAM HODGES

UM News

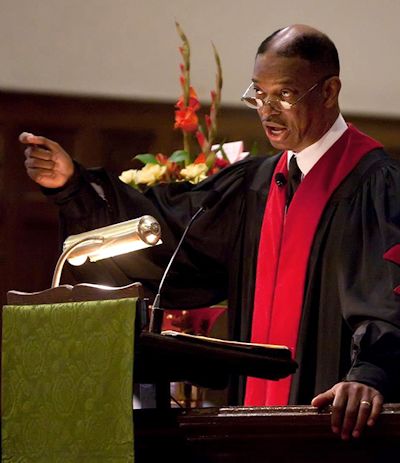

The Rev. Henry Masters has a thing for Simon of Cyrene.

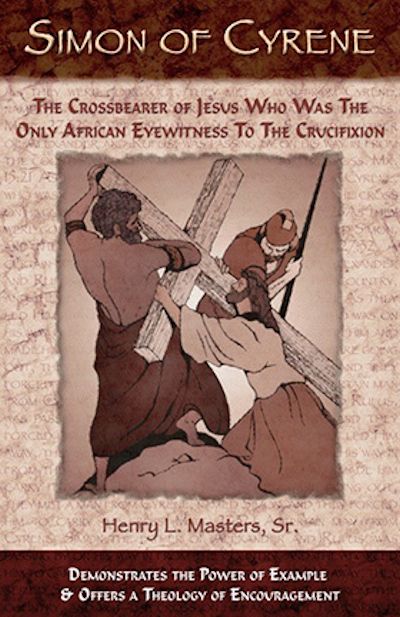

Nearly two decades ago, Masters wrote and published a book about the African man summoned from the crowd to carry Jesus’ cross to Calvary.

Now, at age 76 and retired as a United Methodist pastor, Masters is producing his own full-length musical about Simon of Cyrene. It’s to be performed as a special Lenten program on April 8, at Dallas’ Hamilton Park United Methodist Church.

Others might write Simon off as a bit-part Biblical character, briefly mentioned by three of the gospels. Masters finds him fascinating — and highly relevant in a 21st-century America still struggling with race relations.

“Black men, in particular, get caught in circumstances they didn’t create but have to deal with,” Masters said. “That’s Simon.”

With “Simon of Cyrene: The Musical,” Masters is making his debut as a theatrical director. But he has long studied the history of the Black church.

He’s lived a lot of it, too — as a bridge figure between the eras of segregation and integration; as pastor of prominent Black United Methodist churches in Dallas and Los Angeles; and as publisher of By Faith Magazine, which helps connect Black United Methodist churches across the U.S.

He’s even married to a Black United Methodist pastor, the Rev. Dianna Masters, herself recently retired from ministry in the North Texas Conference.

Among Henry Masters’ fans is the Rev. Sheron Patterson, pastor of Hamilton Park United Methodist Church.

“As long as I have been around the North Texas Conference, Henry has been a leader,” she said. “He is the calm, cool, level-headed type who gets things done without a lot of fanfare.”

Masters grew up in a Methodist family in Waco, TX, during the latter days of Jim Crow.

He recalls that as a teenager he was playing dominoes in a local cafe one day when two white police officers came in and hauled him out to a squad car. A white girl, a rape victim, sat inside. The officers put Masters’ face where she could see it.

“They simply asked one question, and that was, ‘Is he the one?’ And she said, ‘No,’” Masters said in an oral history interview with Southern Methodist University. “And they sent me back in. But all through my life, I have always been reflective of how that situation could have been a tragic turning point. Because all they needed was the girl’s word.”

Masters would go on to graduate from Paul Quinn College, a historically Black school in Texas. He then experienced integrated education for the first time at SMU’s Perkins School of Theology.

This was a period of heightened racial tension and student activism. On May 2, 1969, Masters joined other Black students in demanding that SMU President Willis Tate address their concerns, including a scarcity of Black faculty.

“We met with him,” Masters said. “We weren’t finished, but he felt he was finished, so he left and we stayed in there. We were trying to figure out our next move.” The Black students’ peaceful occupation of the president’s office is part of SMU lore but lasted only a few hours, Masters recalled, and led to modest changes.

Meanwhile, Masters was answering a call to ministry, and race was a big factor as he did so. He and his Perkins roommate, John Greene, would be the last two people ordained in the segregated West Texas Conference of The United Methodist Church.

A community organizer early in his ministry, Masters soon became a local church pastor, mentored and inspired by Black United Methodist legends such as the Rev. Ira B. Loud, the Rev. Zan Wesley Holmes Jr., and the Rev. Negail Riley, founding coordinator of Black Methodists for Church Renewal.

Over more than four decades, Masters would lead three historic predominantly Black United Methodist congregations in Dallas: St. Paul, Hamilton Park and St. Luke “Community.” He had a long stretch as well at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, and he served as a district superintendent in the North Texas Conference.

But he always had more going on. For example, Masters’ interest in literature was sparked by a course taught by Professor Ronald Sleeth at Perkins, and led him to become a keen student of the Harlem Renaissance, including the poet Countee Cullen.

“A lot of people don’t know Countee Cullen was the (unofficially adopted) son of the pastor of Salem Methodist Church,” Masters said of a renowned Harlem church. “He grew up in that church. He was a PK! (Preacher’s Kid.)”

Masters’ pursuit of a doctor of ministry degree at Perkins, which he earned in 1990, had him going deeper into African spirituality, including studying Black theologians and bible scholars, such as James Cone and Cain Hope Felder.

It was in this period that Masters began to focus on Simon the cross-bearer. Though the gospel passages that mention Simon don’t specify his ethnicity, he is described as being from Cyrene — a city in northern Africa. And Masters, with many others in the Black church, believes he must have been dark-skinned.

“I think the color of his skin made a difference,” Masters said. “He’s there (at Jesus’ walk to the crucifixion), and he’s the only African there we know of, in a crowd of Jews and Romans. You can’t stand out any more clearly in a crowd, being a Black person. And he’s the one who gets picked.”

Masters’ short book “Simon of Cyrene” drew endorsements from United Methodist Bishop Gregory Palmer, among others. It continues to be used for Lenten study in United Methodist churches.

On retiring from full-time ministry in 2014, Masters focused on By Faith Magazine, which he still publishes bimonthly. It’s dedicated to the legacy of Harry Hosier, an early, important African American Methodist preacher. (Masters has established a Harry Hosier Award at Perkins, as well.)

But Masters kept thinking about Simon, and about the possibility of a full-length musical. (A smaller-scale musical version of Masters’ book was done at St. Paul United Methodist in Dallas years ago.)

The desire to connect Simon to the challenges of today — especially the persistence of unarmed Black males dying at the hands of police — gave added impetus.

Masters wrote a goal for his project: “To use the music created around the biblical story of Simon of Cyrene (a Black African) to demonstrate to other Black boys and men how God works miracles to turn circumstances and situations into God-honoring destinies.”

In Masters’ musical, Simon is a family man and spice trader who makes a business trip to Jerusalem, leading to a life-changing encounter with Jesus. Masters stresses that Simon bore Jesus’ cross unwillingly, but was transformed.

Masters intersperses the story with spirituals, songs of his own (he wrote the lyrics and got help with the music from a local recording studio) and musical settings of familiar texts, including the Wesleyan Covenant Prayer. The score draws from a Countee Cullen poem written from the perspective of Simon of Cyrene. It includes African dance, and a range of stirring readings, from the Bible and other sources.

Most of the cast members come from Hamilton Park United Methodist Church, but for Jesus, Masters enlisted Malcolm Payne Jr., who has sung with the Dallas Opera and Fort Worth Opera.

“It’s a pretty cool project,” Payne said. “I personally have been super interested in seeing more modern takes on biblical stories.”

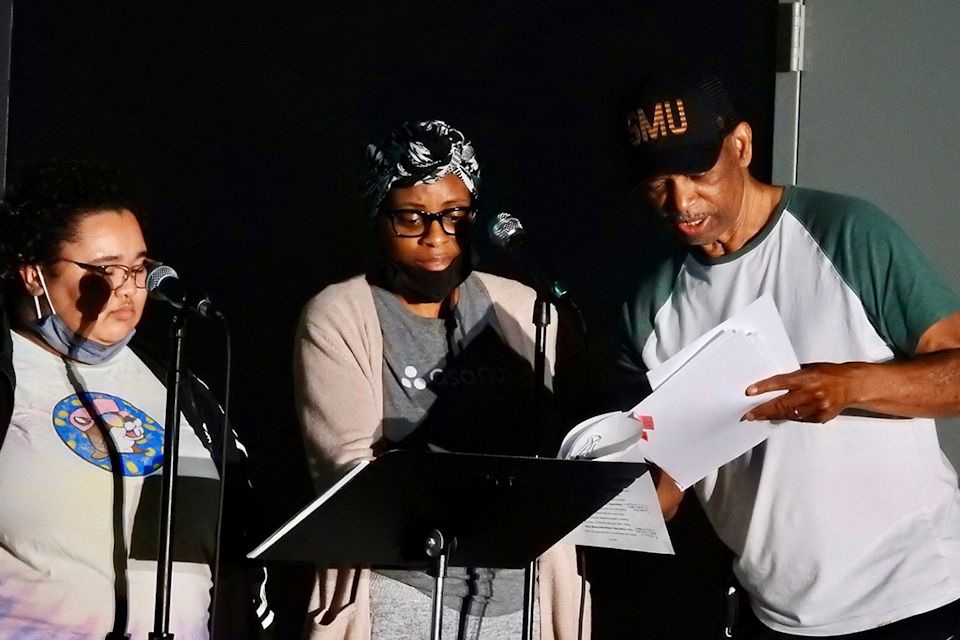

At a rehearsal earlier this week, Masters was on and off the stage, giving direction to Payne and other cast members, and dealing with a range of technical issues. He stayed calm and carried on.

There may be bumps in the April 8 performance, but he has no doubts that a musical is a fitting way to honor Simon and the Black church.

“Music is such an integral part of our history,” Masters said. “It’s a cultural underpinning of our struggles and our joys.”

Last Updated on September 20, 2022