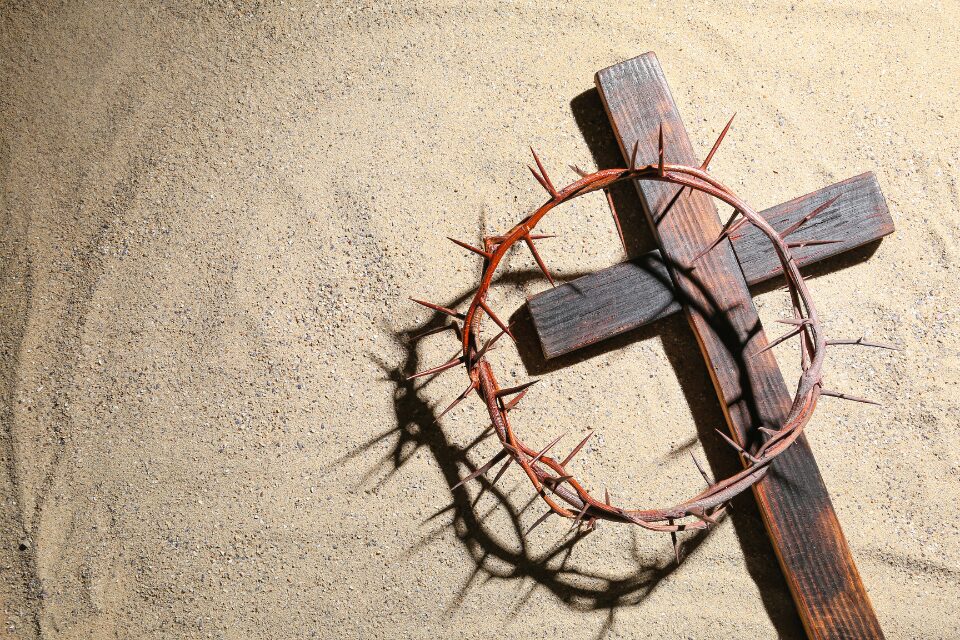

Rev. Paul Hahm walks us through the theological spectrum of meanings ascribed to Good Friday, inviting us to embrace them all.

REV. PAUL HAHM

Farmington: Orchard UMC

Full disclosure: I grew up in The United Methodist Church because my father is a retired elder. While faith was an important part of my upbringing, I only had a vague understanding of Christian concepts. For example, what could be good about Jesus dying on a Friday? From adolescence to college, seminary, and ministry, my understanding of Good Friday has grown richer and more encompassing. So, I’d like to briefly take you through my journey of what made Good Friday a good day.

Good Friday

As a young child, I always found it confusing that the day Jesus died was considered a good day. Yet, in the evangelical branch of United Methodism, it was explained to me that it was indeed a good thing that Jesus died because he bore the punishment of humanity’s sins: my sins. Within the framework of crime and punishment, it was good indeed that I avoided God’s wrath. It was like starting a fight with my older sister, but she got in trouble instead of me.

God Friday

As I grew older, there was further proselytizing that not only was Jesus’ death good, but it was all part of God’s plan to save humanity. Some have cited a 1909 entry in a Roman Catholic encyclopedia indicating that the name “Good Friday” is a derivative of the phrase “God’s Friday.” In this framework, being all-powerful and omniscient, God knew the story would not end on Friday, as Jesus’ death was a mechanism to fulfill God’s demand for punishment for our sins.

From a critical perspective, the idea that God makes the rules and these rules demand the death of God’s son feels cruel and abusive. From a generous perspective, I understand the liberation one might feel from knowing that there is no debt to be paid or impending doom because of our wrongdoings.

Holy Friday

However, most English language experts agree that the etymology of Good Friday neither points to our modern definition of the word “good,” meaning pleasing or desirable, nor is a corruption of the word “God.” Instead, linguistics professor Anatoly Liberman at the University of Minnesota and Jesse Sheidlower, the president of the American Dialect Society, confer that an antiquated meaning for the word “good” is to be holy or sacred. This opens up another possibility to understand the meaning of Good Friday, one I encountered through learning in seminary and ministry.

A New Vision

During the Roman Empire, crucifixion was a public form of execution to be used as a deterrent against political dissidents and violent criminals. Episcopal priest Marianne Borg writes, “Crucifixion intended to drive out the memory of that person. Because remembering was too horrible. Too traumatizing. Who would want to remember that horrible end? Who would consider talking about that person ever again? No one. That was the goal. The victim was silenced. And those associated with the victim fell to silence as well. A social silence. No stories about them would be told again. After all, the person had been eliminated. All memory of them was to be forsaken. End of story. End of stories.”

Jesus was not a violent criminal, but his messages and popularity represented a challenge to the Roman political system. Rome ruled through conquest, brought peace through military victory, and maintained social structures through exploitive taxation. Jesus saw an alternative vision of God’s reign: the powerful served the weak, the wealthy cared for the poor, and the religious advocated for the marginalized and ritually unclean.

Unlike a kingdom, a vertical structure of hierarchical power, Jesus envisioned a kin-dom, a horizontal structure of shared power. The kin-dom was to be both a utopian ideal and a way of living meant to be practiced in the present. Jesus believed in this holy, set-apart vision and chose not to participate in the systemic cruelty he was living in. Jesus rejected Satan’s promise of ruling over the kingdoms of the world. The world’s kingdoms feared leaders of radical movements. They feared that people might begin to imagine an alternative vision. Systems of power silence people like Jesus because they expose the hopeless, unbridgeable disparity that the people must live in to support the handful of very powerful people.

Which Story Is the Right Story?

Despite the seemingly chronological order of my faith journey, I try to generously embrace the theological spectrum of meanings ascribed to Good/God/Holy Friday. I hope and pray that we can all embrace the variety of theologies, experiences, and understandings we all have to unite us in these contentious times. May we be holy examples of the manifestation of Jesus’ alternate vision for the world today.

Despite the empire’s attempt to silence and eliminate Jesus’ vision, thousands of years later, we’re still here reflecting, pontificating, and dissecting this story in new and meaningful ways . . . and we haven’t even reached Sunday yet.

Last Updated on April 3, 2024