Pastors serving in cross-cultural ministries, including several from Michigan, recently gathered in Atlanta to offer each other support and strategies for navigating challenges.

JIM PATTERSON

UM News

Proud Americans in a predominantly white United Methodist church outside Atlanta fly an American flag to mark Veterans Day.

Who would object? You might be surprised to find out that such flag-flying could alarm non-white residents of the neighborhood. In the eyes of some, the American flag has been co-opted by white supremacists and far-right groups as a symbol, clouding the waters for patriotic Americans.

“One of the ways that people of color identify a potentially racist scenario is when they see a church that is an all-white church and they’re particularly passionate about the American flag,” said the Rev. Tony Phillips, associate pastor of Bethany United Methodist Church in Smyrna, Georgia.

Phillips, who is Black, has a calling to bring diversity to churches like Bethany where membership does not represent the multicultural communities in which they are set.

“It’s gentle conversations,” he said. “You’re looking at that flag, and you’re like, ‘Gosh, we shouldn't put that out there.’ But you can’t remove it because it would cause so much friction [that] Fox News would be down there.”

Such issues pop up “left and right,” he added.

“There’s a group going on a field trip, and they’re going to the ‘Gone with the Wind’ Museum,” he said. “Of course, that’s probably not something that people in our [non-white] community are going to embrace.”

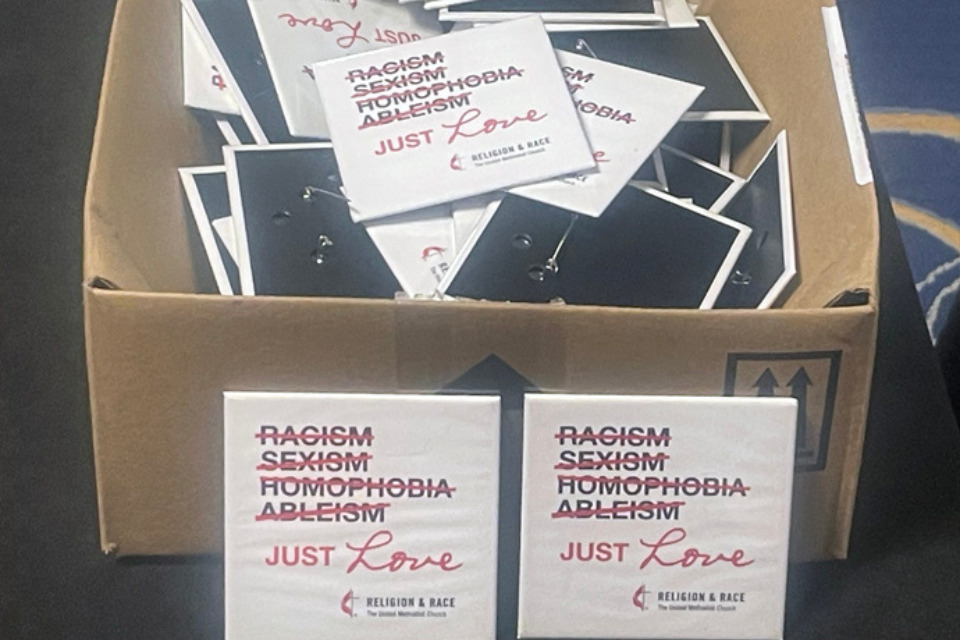

Discussions like this abounded at the Facing the Future conference, held November 14-16, 2023, in a downtown Atlanta hotel. The United Methodist General Commission on Religion and Race event drew about 300 attendees, mostly United Methodist pastors serving in cross-cultural ministries. The goals of the conference included offering support and affirmation and providing practical workshops to help pastors in such ministries.

There were expressions of hurt and hope.

“This is the reality of cross-racial, cross-cultural ministry,” said the Rev. Giovanni Arroyo, top executive at Religion and Race. “One of the reasons why this conference came into existence is, ‘How do we create a place that contains space where this group of leaders across the church could actually be vulnerable, and not feel like this can be used against them?’”

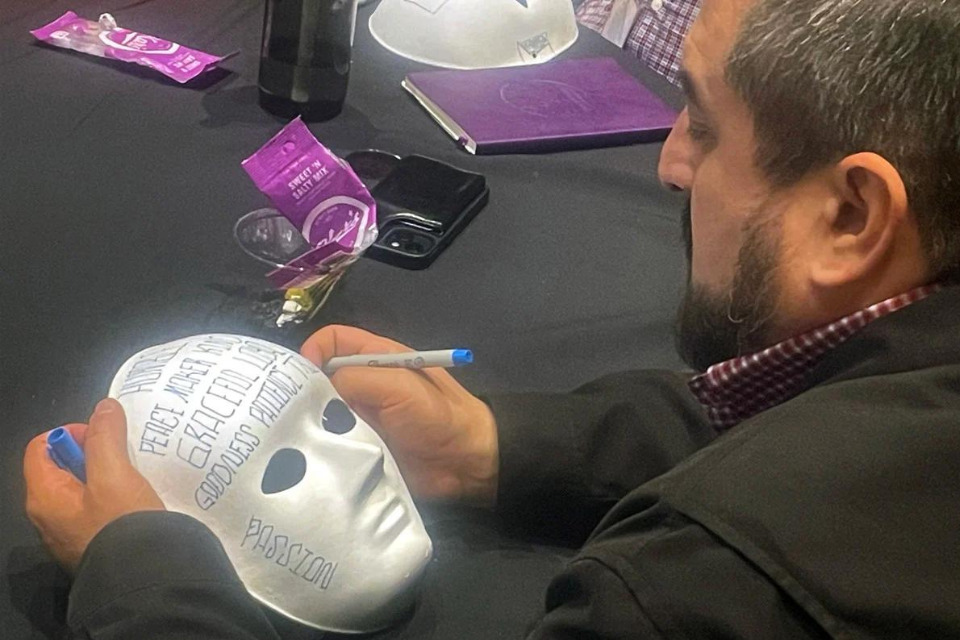

In a revealing exercise during the conference, blank masks were distributed to the pastors, who were invited to decorate them with colored markers. The outside of the mask was to express the face they show to the outside world, while the inner mask was to reflect how they wish others would perceive them.

“We may go in wearing a mask to do what God has called us to do, because we can’t fully walk into who we are in our ethnicity,” said the Rev. Dyanne Corey, an elder in Virginia. “I want to be in a place where I am embraced for who I am, and I can preach the way God birthed me to preach — and to feel the joy again of my call.”

Pastor Miriam Peralta, who has been appointed to Lawrence United Methodist Church in Lawrence, Michigan, which is mostly white, but is also working with her husband, Cesar Garcia, to start a Spanish-speaking faith community among migrant workers in southwest Michigan, reflected on the mask exercise.

She spoke about the complex thoughts and feelings she has working in different congregational contexts as a bicultural person.

Peralta explained, “This [mask-making] exercise helped me realize who I am as a bicultural person, embracing both the joys and the pains of being a 1.5 generation [came to the United States in her early teens]. Sometimes people expect me to be in one culture or function in that culture, when the reality is I am both. I can sing in Spanish, and I am able to understand that part that connects me to my Mexican heritage, but I can also sing in English and understand the culture in which I grew up.”

Being able to embrace who she is and continue to serve and answer her call to ministry was the beauty of the mask-making exercise.

“Even when we may feel that we may not fit in either culture,” she noted, “God says and reminds us that the calling comes from God alone, who is above all cultures and the creator of all cultures.”

Dawn Houser, pastor of Aitkin United Methodist Church in Aitkin, Minnesota, is a Native American leader at the majority white church.

Houser said her name and appearance give her the option to hide or downplay her Native American background, but she doesn’t do that.

“When I started the appointment there, they did not know that I was Native American,” Houser said. “They’re a good group of folks,” she added. “It’s interesting for them. I don’t think they consider my appointment to be a cross-cultural appointment.”

Her heritage does make her approach to Christianity a little different.

She prefers to preach about the story of Native Americans rather than that of the Israelites of the Old Testament, and she doesn’t refer to Jesus as “Lord.”

“To people who have been colonized, it’s a real problem,” she said. “[Not using Lord] doesn’t have anything to do with Jesus. [Native Americans] would take it as a slight toward Jesus.”

Houser reports receiving racist threats from people outside the church, including threats of violence.

Workshops at the conference included “Navigating Bias,” “How to Lead an Emotionally Intelligent Church,” and “Empathy and Burnout.” The emphasis was on giving tools to pastors who are weary because of the hard circumstances of their jobs.

“I think the question [of the conference] is, ‘Are we trying to change people back home, or are we trying to create space for us to recognize and deal with our pain?’” Arroyo said.

“We have to recognize who we are and where we are,” he added. “Then it could be better able to navigate when we go back.”

The Rev. Gunsoo Jung, pastor of First United Methodist Church and Emmanuel United Methodist Church, both in Blissfield, Michigan, spoke of the pain he has encountered as a Korean pastor from certain individuals at predominately white churches he’s served.

“The discrimination and contempt that I have encountered,” said Jung, “from certain congregants in my capacity as a pastor have undermined my vocation to the ministry and caused me to experience frustration.”

He came to the Facing the Future conference feeling afflicted and agitated due to the inappropriate behavior and words of some of his church members. He had a hard time fitting in at first. But then the conference gave him a gift — the encouragement and fellowship of other United Methodist pastors and lay leaders who found themselves in similar situations.

Jung said, “The conference refreshed both my spirit and physical being, providing a much-needed respite . . . . I was especially uplifted and consoled by the numerous laypeople and pastors who shared their suffering and experiences with me throughout the conference. . . . I found them to be not only a source of great solace and inspiration but also a source of fresh challenges that will shape my future ministry and life.”

Some pastors of color say they sense a racial component in their struggle to even get ordained.

“I’ve been in the board ministry ordination process for a long time,” said Eric Reniva, the Filipino and Puerto Rican pastor of Waterman United Methodist Church in Waterman, Illinois. “My biggest gripe is that you’re good enough to lead a local church, but you’re not good enough to be ordained.”

He said he has seen white pastors have a smooth journey through the ordination process and get plum appointments, especially legacy pastors — those with family members who have held positions of authority in The United Methodist Church.

But not him.

“There’s always something wrong with your answers,” Reniva said. “You’re not Wesleyan enough, or you don’t understand this or that, or you don’t have a great explanation for [the Book of] Discipline and polity.

“When they were talking about systems that hold you down and make you fearful, that’s one of them for me.”

Arroyo says he has had similar feelings, despite rising to be a top church official.

“I think as a person of color, I know that I have to work harder than my siblings who are white, just so that I could be seen that I’m almost equal to the leadership — almost.”

Being vocal about racial issues doesn’t seem to be a good option, Reniva said.

“I’ve experienced it in seminary, and I’ve experienced it in my own personal ministry,” he said. “When you preach truth to power, you get stomped on. I mean, you may get punished for it.”

The Rev. Jennifer Jue, pastor of three United Methodist congregations in Jackson, Michigan: Brookside, Trinity, and Calvary, outlined challenges that the commissioning and ordination process has given ethnic-minority candidates in the Michigan Conference.

“I served on the Board of Ordained Ministry for nine years,” she said, “and the reasons for ethnic-minority candidates and international candidates who were deferred and got a ‘wait’ were complicated. I wondered what reasons were related to cultural differences and miscommunication. Many of those who got a ‘wait’ chose not to interview with the board again and remained a licensed local pastor, and so we have low numbers of ordained ethnic-minority clergy in our conference.”

Jue hopes that the Michigan Conference Board of Ordained Ministry and the District Committees on Ordained Ministry will increase their membership’s ethnic-racial diversity and engage in anti-bias, anti-racism training for the committees.

“I’d also recommend that the Board of Ordained Ministry review and evaluate those candidates that got a ‘wait’ and then analyze and offer the support and guidance necessary for them to proceed successfully through the ordination process,” she concluded.

Not all the pastors at the conference are struggling. But the Rev. Grace Han, a Korean pastor at historically white Trinity United Methodist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, says some issues remain.

Han, the daughter of two United Methodist clergy, has noticed that nobody ever assumes she’s the pastor of the church. She has to tell them. And tricky discussions do come up.

“I was at my church when George Floyd was murdered, and in light of all of the Black Lives Matter movements, I’ve tried to have some really honest conversations about how we think about race, how we talk about race, and how we address racism, especially when it’s right on our [television] screens for everyone to see.”

She has begun having those conversations, but more are needed, she said.

“I don't want to paint it as like a perfect situation,” Han said. “I recognize that I’ve been blessed in my context, and I appreciate that and I value that.

“So there are success stories, and not just painful ones.”

The Rev. YooJin Kim, pastor of Wacousta: Community UMC in Eagle, Michigan, reiterated that some congregations like hers are doing better at cross-cultural and cross-racial bridge building where the pastor and congregation have different cultural backgrounds.

“The church where I serve is very open,” she explained, “and exhibits genuine interest and curiosity about Korea, the home country of their pastor, and enjoys learning and engaging with my culture. This mutual interest creates a dynamic cross-cultural exchange where we find fascination in each other’s cultures and narratives, fostering a deeper understanding. As an example, I am currently preparing a Korean food class that involves both cooking and tasting.”

Arroyo said that individuals and organizations like the Commission on Religion and Race “have to keep on pushing.”

“We are called to do better, so that we can move on to the gospel of Jesus Christ, which is love. I think that’s important.”

The Rev. Beatrice Alghali grew up in Kenya and is now serving churches in the Michigan Conference. She is currently the pastor of Northlake United Methodist Church in Chelsea, Michigan. Alghali is hopeful for The United Methodist Church as it presses on and becomes the people God has called us to be.

“Diversity is our strength as a church that looks for growth. The Michigan Conference is doing its best, but there is still a lot to be done.”

She concluded, “A more inclusive paradigm urging us to reconcile seemingly disparate concepts such as self-care and neighborly love must be looked at. . . . We need more conversation with laity on diversity . . . . We need myriad lessons gleaned from the communal meals together and casual table conversations to hear the ‘fate’ of cross-cultural clergy.”

Alghali believes transformation happens best around tables, sharing meals and conversation, and learning about one another. And the Facing the Future conference gave a foretaste of what is possible with God’s help.

James Deaton, Content Editor for the Michigan Conference, contributed to this report.

Last Updated on January 24, 2024