After fleeing war and disease in Africa, Liberians now living in the U.S. fear job loss and deportation.

BARBARA DUNLAP-BERG

United Methodist News Service

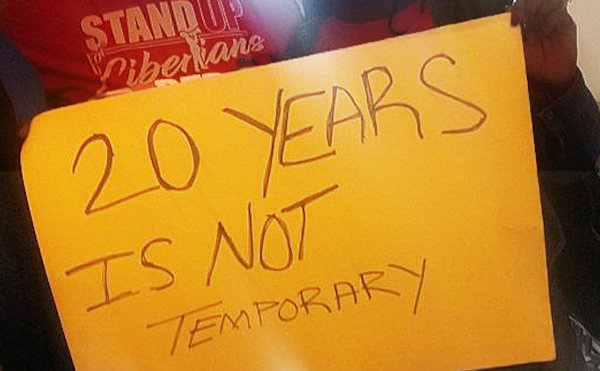

The future of an estimated 5,000 Liberians temporarily living in the United States is in jeopardy after President Donald Trump terminated the Deferred Enforced Departure for Liberia, effective a year from now on March 31, 2019.

Liberian United Methodists are among those affected and some church leaders participated in a letter-writing campaign asking Congress to extend the program.

Former President Bill Clinton first authorized DED for Liberians following civil war in the West African country. Former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama repeatedly extended the program. DED is not a specific immigration status, but for a designated period of time that DED holders are not subject to removal from the U.S.

The news came on March 27, just four days before the deadline to extend the humanitarian program. In a presidential memorandum, Trump cited improved conditions in Liberia.

“Liberia is no longer experiencing armed conflict and has made significant progress in restoring stability and democratic governance,” he said. “Liberia has also concluded reconstruction from prior conflicts, which has contributed significantly to an environment that is able to handle adequately the return of its nationals.” Trump noted that since the 2014 Ebola outbreak, “Liberia has made tremendous progress in its ability to diagnose and contain future outbreaks.”

While the effective termination date was delayed to March 31, 2019, “to provide Liberia’s government with time to reintegrate its returning citizens,” DED beneficiaries who do not qualify for other forms of immigration relief will have only a year “to seek an alternative lawful immigration status in the United States, if eligible, or, if necessary, to arrange for their departure.”

The decision directly affects DED holder Nancy Harris, who teaches at the United Methodist-related Highlands Child Development Center in Birmingham, Alabama.

During the seven-year civil war that erupted in Liberia in 1989, Harris’ husband found a job in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. “We moved there with our two daughters,” she recalled, “and lived there for about six years.”

Refuge in the U.S.

The war claimed more than 200,000 lives and displaced over half of the Liberian population. Food production halted, and the country’s infrastructure and economy were destroyed. A second civil war followed from 1999 to 2003. Then in 2014, Ebola challenged Liberia’s recovering health system.

During these crises, thousands of Liberians sought refuge in the U.S.

“We got a visitor visa to the United States,” Harris said. “We now had three daughters. A church in Alabama offered my husband a job as a pastor and an opportunity to go to school. The war continued, and we needed a stable home. My husband and I applied for Temporary Protected Status.”

During the past 25 years, many Liberians like the Harrises have gone to school, developed careers and raised families in the U.S. However, now they risk either being deported to a country where they have not been in decades or living as undocumented Americans.

The Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in 2012, allowing undocumented young people brought to the U.S. illegally by their parents to get a temporary reprieve from deportation and to receive permission to work, study and obtain driver’s licenses.

“Our two oldest daughters,” Harris said, “were approved for DACA. They are married now and have applied for green cards through their partners.

“Our youngest daughter was recently approved for DACA and now awaits her EAD (work permit) card.” Now in college, the 19-year-old used her approval letter to get a job and acceptance in school. Harris pointed out that in the family’s situation, their daughter doesn’t qualify for financial aid.

“She cannot get a personal loan from a bank to finance her education,” Harris noted. “She has to work a lot to pay for tuition at $350 to $400 per credit.”

‘I want to stay’

Harris has a degree in religious education with emphasis on reading and work with preschoolers. At the child-development center, she said, “We have a Christian curriculum, and the lessons are tied to early literacy. The parents of the kids I work with want me to stay.”

Her dream is to return to school to obtain a master’s degree in education/curriculum development so she can serve African immigrants like herself.

“I volunteer in a program that helps in literacy in the community,” Harris said. “I want to stay in Alabama and continue doing that.”

Her earnings of $16.75 an hour must stretch far. Her husband’s TPS status expired, so he cannot work.

“A lot of people are depending on me,” she said. The oldest of 10 children, Harris also supports a niece who was orphaned in Liberia and a brother who attends a university there. “My dad,” she added, “is back in Liberia and has an enlarged heart. I have to work to get him meds. Every two weeks I send $150.”

The Rev. Jeania Ree V. Moore, who manages civil and human rights advocacy for the United Methodist Board of Church and Society, said faith leaders and organizations participated in a bicameral, bipartisan letter-writing campaign to Congressional representatives, urging another DED extension. In a letter to their colleagues, four members of Congress also sought support.

Minnesota is home to an estimated 25,000 Liberians. Advocates like the Minnesota-based Black Immigrant Collective are pushing for a more permanent solution for the Liberians they serve.

“They are tax-paying Americans who have made homes and families in different parts of the country,” said a spokesperson, who asked not to be identified.

Last Updated on December 28, 2022