In the two years since Liberia was declared Ebola-free, United Methodist schools and hospitals have helped the country recover.

JOEY BUTLER

United Methodist News Service

Reports of a recent outbreak of Ebola leading to 25 deaths in the Democratic Republic of Congo has brought the disease back into international headlines, just two years after the epidemic that killed more than 11,300 people in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Liberians continue to recover from that crisis even though the country was declared Ebola-free in January 2016. The road back to “normal” has been a long one.

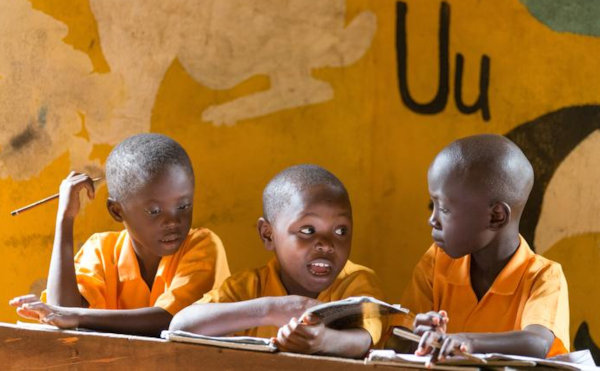

One of the areas hardest hit by the crisis was education. With the entire country seemingly at a standstill while trying to halt spread of the disease, schools were closed from August 2015 until February 2016. The loss of most of a school year put students behind, and when schools reopened, many students lacked the fees to return because their parents had been out of work during that time or may have succumbed to the disease.

“At first, it was hard bringing the children back,” said the Rev. Charles Fiske, principal of the school at the Bishop Judith Craig Children’s Village in Duahzon. “Many were traumatized in the same way as if there were a war in the country. Bringing things back to a sense of normality takes a lot of effort.”

When Ganta United Methodist School reopened after the five-month closure, fees for students were waived, which resulted in a shortfall of $2 million LRD (about $14,500 USD), said James Y. Koroloroblee, the school’s interim acting principal.

“We had to find a means for people to pay so we offered jobs cleaning the campus during vacation time in exchange for fees. We had to keep them in school,” he said.

Abullah Buhmean, a 17-year-old student at the school when United Methodist News Service interviewed him in June 2017, was one of the students who benefited from a work grant.

“My uncle was sponsoring (my school fees) and when he died because of the Ebola, there was no way for me to continue school, so the school put me on work grant scholarship,” Buhmean said. “As a work grant student, I am responsible for cutting the grass around campus.”

While teachers and faculty were trying to help students regain their lost lesson time, many of them were also coping with personal difficulties brought on by the Ebola epidemic.

Ernest Tokpah, an agriculture field supervisor at the school, told UMNS in June 2017 that he had adopted his sister’s four children after both she and her husband died from the disease. Stigma about Ebola made an already difficult situation even harder to deal with.

“When my sister and her husband died and I brought the children home, the entire community shunned me and the children, and we were left to do things on our own,” he said.

Tokpah said that fear and lack of credible health information led people to alter almost every facet of daily life.

“Ganta was on fire because of the Ebola,” he said. “We stopped eating together, we stopped shaking hands, and people practically stopped talking to each other.”

Johnson N. Gwaikolo, former president of United Methodist University in Monrovia and now a member of Liberia’s Legislature, told UMNS in June 2017 that Ebola set the school back, and reported losing three or four students to the disease.

“Every academic semester we project our estimated enrollment,” Gwaikolo said. “Approaching the start of school, we had half our estimate, so it delayed our calendar year.”

The university added several hours to class time to catch up, and offered payment plans to students struggling to come up with funds for tuition.

The church also played a role on the medical front line of the outbreak.

David N. Vulu, human resources director at Ganta United Methodist Hospital, said, “There came a point where some areas were no-go because of the intensity of the Ebola crisis.”

Vulu said one person affected by the situation got on the radio, frustrated that he was kept in his home with no support.

“The district superintendent of the church here took a team to talk to this guy and provide support,” he said. “The church helped with witness and helping health facilities to carry supplies.”

Ganta Hospital is in a fairly remote area. The next hospital to the north is 26 miles away; a specialized hospital is about 60 miles away. When the breakout occurred, hospital staff mobilized to address the crisis.

When the number of Ebola patients rose dramatically and there was no Ebola Treatment Unit set up yet, the hospital allowed the local government to use its eye clinic. Later, the Nimba County Health team and Project Concern International constructed a large containment facility on a nearby rural airstrip. Ganta Hospital staff assisted the medical team running the facility.

Eye and vision problems have surfaced in Ebola survivors, but Ganta’s eye clinic tends to refer anyone with such issues to a facility in Monrovia.

“Their treatment is a specialized process and we’re not equipped to provide services for them,” said Clarence Menleh, supervisor of the eye clinic.

As the hospital lacks a facility to fully isolate patients, its role is often one of referring patients elsewhere. There have been no confirmed cases of Ebola since the outbreak was declared over, but staff now have procedures in place, said Agatha Neufville, the hospital’s director of nursing.

“Before Ebola, patients could just walk in. After, we decided to do screening and triage.”

They take everyone’s vitals and temperatures. Even visitors have their temperature taken before being allowed in. Patients with fever are placed in a separate area and staff are required to don preventative materials before seeing those patients. If symptoms don’t get better after a few days, patients are transferred to clinics better suited to issues like hemorrhagic fever.

“It was a challenge, not knowing facts about Ebola and you have to keep working with minimal supplies,” Neufville said. “It was not easy but at the end, God was with us and we worked.”

Last Updated on November 9, 2023