A Colorado pastor, Norman Mark, remembers attending four Indian boarding schools during his youth. “It was the loneliest time in my life,” he says.

JIM PATTERSON

UM News

At a shopping mall waiting for his grandchildren, Pastor Norman Mark descended into dark memories of his childhood, when he lived at schools intent on annihilating his connection to his Native American culture so he could be more useful to white people.

At a shopping mall waiting for his grandchildren, Pastor Norman Mark descended into dark memories of his childhood, when he lived at schools intent on annihilating his connection to his Native American culture so he could be more useful to white people.

“I will see to it that nothing like this ever happens to my grandchildren,” he said during a telephone interview with United Methodist News.

Mark, a Navajo and United Methodist pastor with a three-point charge in Colorado, attended four Indian boarding schools during his youth. There he witnessed beatings and students having their mouths washed with soap when they spoke their native language. There was also sexual abuse, a poor diet, and some students being forced to fight each other for the staff’s entertainment.

“It was the loneliest time in my life,” said Mark, 65. “It was horrible living my early life. Sometimes it’s shaming to talk about it.”

His mother was pressured into allowing him to be taken away by threats to cut off her monthly check from the government.

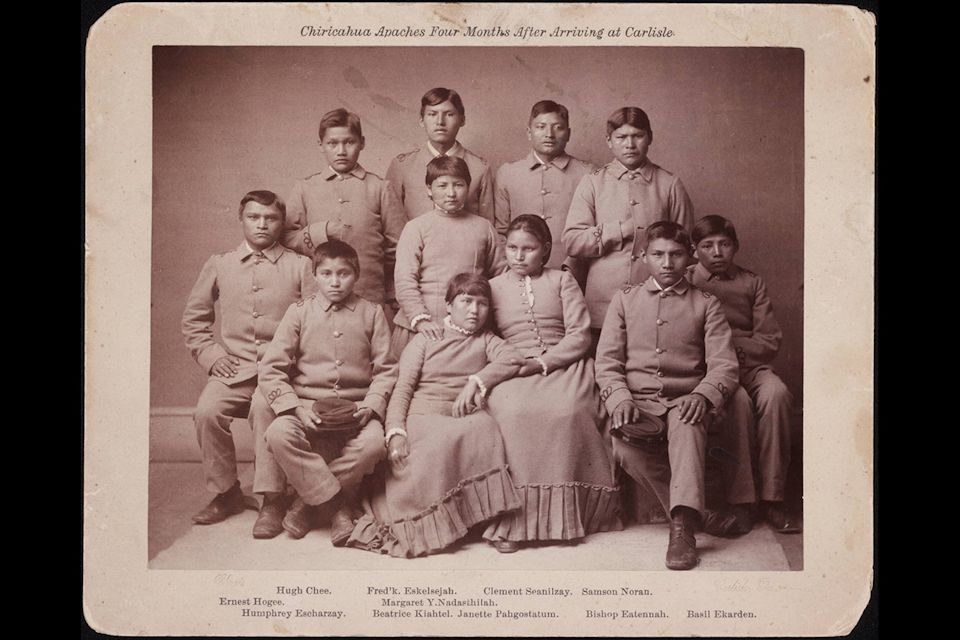

The theory of the schools, as articulated by Capt. Richard H. Pratt, who founded the first Indian boarding school in Carlisle, PA, was “Kill the Indian, and Save the Man.”

The boarding schools “were very strictly run, around the principles of corporal punishment,” said Tink Tinker, a member of the Osage Nation and professor emeritus at Iliff School of Theology. Tinker wrote the preface of Ward Churchill’s 2004 book “Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools.”

“Pure and simple, these were not educational facilities,” he said. “They were training Indian children for manual labor, just to serve their white superiors.”

Graduates from the Carlisle school had to take an oath to profess that they were no longer Indian in order to get their diplomas, Tinker said.

Some Indian boarding schools were established by Methodists, including The Shawnee Methodist Indian Manual Labor School in Fairway, KS, and Asbury Manual Labor School in Fort Mitchell, AL.

In June, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced an investigation into Indian boarding schools, with an emphasis on cemeteries and potential burial sites. The discovery of 215 unmarked Native American graves in Canada prompted the U.S investigation, said Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary.

She said the investigation “will address the intergenerational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be.”

Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879, according to “Giving Our Hearts Away: Native American Survival” by Thom White Wolf Fassett.

“Older Indians, Pratt argued, were beyond salvation,” wrote Fassett in the 2008 book. “But the young, separated from the influence of home and tribe, forced to give up their native tongue and culture, immersed in the habits and beliefs of white Americans and taught useful trades and skills, could become functioning, self-reliant adults like other Americans.”

Pupils were forced to cut their hair and wear Western-style clothing.

“Modern scholars would note that with the advent of institutionalized Indian education, Indian children have contracted dietary diseases, learned to despise their ancestors, their culture, their religions, and their traditional values,” Fassett wrote.

The schools operated through the 1960s, and there are still some to this day. Now operated by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education, the modern schools “provide a quality education to students from across Indian country and empower Indigenous youth to better themselves and their communities as they seek to practice their spirituality, learn their language and carry their culture forward,” according to the Interior Department.

The Native American Comprehensive Plan of The United Methodist Church is a direct result of the boarding schools, said the Rev. Chebon Kernell, executive director.

“We’re here simply because a harm has been inflicted, and we’re trying to help communities recover from that harm and not to harm any more in the future,” Kernell said.

Reparations should be on the table, but not direct distribution of money to individuals, he said.

“(Reparations should) help to support those grassroots entities, sometimes tribal government entities, that are trying to reconstruct what was destroyed by those boarding schools: our language programs, our cultural centers, all of these kinds of things,” Kernell said. “How can we partner with them as a denomination to help us rebuild?”

Tinker would prefer something more basic: the return of some of the land that was taken away from Native Americans.

“States and the federal government are in possession of huge tracts of land that are not a part of your Christian private property,” Tinker said. “Give those lands back to Indian people.”

For example, the Black Hills of South Dakota should be returned to the Sioux, Tinker said.

“It belongs to them by treaty,” he said. “Let them use it however they want and it can still be a tourist designation and recreation site for white people. But give it to the Sioux along with a budget to run it.”

Tinker also suggests that some national parks land could be returned to the appropriate Indian tribes.

“Those lands are transferable,” he said. “Your home and the lot it’s built on is more problematic. That’s not so easily transferred without hurting you.”

Back at the Colorado mall, Norman is still waiting on some of his 20 grandchildren to finish buying clothing for the new school year. He reflects that many of his peers from the boarding schools are long dead now, many from alcoholism. He believes those were protracted suicides.

Norman had a drinking problem himself for years. He attributes some of his success in life to his 12-year stint in the Army, where he was a paratrooper at the end of the Vietnam War.

Today, he is the pastor of two churches, Johnson Memorial United Methodist Church in Dolores and Dove Creek First United Methodist Church, both in Colorado. He is associate pastor of a third, Cortez First United Methodist Church in Cortez, Colorado.

The past haunts him, though. He is a quiet man, still not able to shake his boarding school training to speak only when spoken to. He still mourns the lack of a mother’s love he felt as a boy, although he knows now that she did indeed love him.

“I understand why Mom let me go to the boarding school,” he said. “The pressure she felt.”

He hasn’t told the grandkids about his boarding school experience, not wanting to burden them.

“Maybe one day if they ask, I’ll tell them,” Norman said.

~ The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition provides this map showing the 367 American Indian Boarding Schools across 29 states, including five in Michigan. Seventy-three remain open today.

Last Updated on November 1, 2023