The Rev. Gil Caldwell’s death on September 4 follows the passing this year of other giants of the civil rights era — the Rev. Joseph Lowery, the Rev. C. T. Vivian, and Rep. John Lewis.

HEATHER HAHN

UM News

The Rev. Gilbert H. Caldwell called himself a “foot soldier” in the U.S. civil rights movement. But many across his beloved United Methodist Church remember him as a general for justice.

He died Sept. 4 in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in hospice care. He was 86.

Caldwell, who went by Gil, pushed to end discrimination throughout a ministry that spanned more than 60 years and churches in at least five conferences.

He tirelessly and nonviolently advocated for both racial and LGBTQ equality — even when doing so put him at odds with prevailing state and church laws. As Caldwell saw it, he was following the call of Jesus to be inclusive.

“He was gentle but strong, wise but humble,” said retired Bishop Woodie White, who considered Caldwell a mentor, model and friend. “His commitment to racial justice and inclusiveness was unyielding, whether in the church or nation.”

Caldwell participated in many of the civil rights movement’s landmark events — the March on Washington in 1963, the Mississippi Freedom Summer voter drives in 1964, the March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965 and the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.

Within his denomination, Caldwell — a co-founder of Black Methodists for Church Renewal — also took an activist role.

“Gil’s passion for equality, justice and inclusiveness inspired others to embrace his dream of beloved community,” said the Rev. Don Messer, president emeritus of Iliff School of Theology in Denver and Caldwell’s friend of more than 56 years.

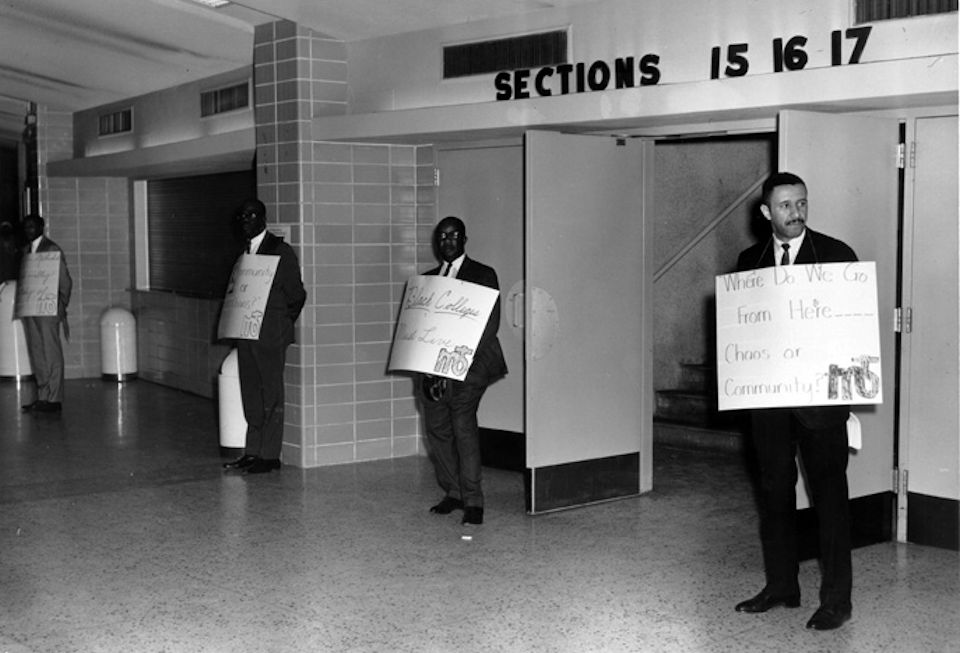

In 1968, Caldwell was among the silent demonstrators standing at the doorway to the Uniting Conference that formed The United Methodist Church and officially ended the Central Jurisdiction that segregated Black Methodists. Caldwell, a newly named district superintendent at the time, held a sign quoting the title of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final book: “Where Do We Go from Here… Chaos or Community?” It was just weeks after King’s assassination.

At the 2000 General Conference, he was among more than 180 people arrested for engaging in civil disobedience to protest the denomination’s stance against same-gender marriage and “self-avowed practicing” gay clergy.

Caldwell remained a passionate nonviolent activist until the end of his life. With help from a walker, he took the podium at a Black Lives Matter rally on June 7 in the New Jersey township of Willingboro.

Bishop John Schol, who leads the Greater New Jersey Conference, introduced Caldwell at the rally. The two had been friends since they were both pastors in the neighboring Eastern Pennsylvania Conference.

“Rev. Gil Caldwell brought the best of both prophetic and pastoral leadership to ministry,” Schol told United Methodist News.

“His love of God motivated him to care deeply for all people and he was a champion for the rights and inclusion of people of color, the LGBTQ community and women. He was gifted at loving, nudging and challenging people to do the just and right thing.”

Caldwell was born in 1933 in Greensboro, North Carolina, the son and grandson of itinerant Methodist pastors. Both he and his father were named for the 19th century white Methodist Bishop Gilbert Haven, a noted abolitionist and advocate for women’s suffrage.

Caldwell grew up in segregated neighborhoods, segregated schools and a segregated church. Early on, Caldwell committed to change that.

After earning an undergraduate degree from North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black institution, he tried to break the cycle of inequality by applying in 1955 to Duke Divinity School in Durham, NC.

However, the Methodist school — which would not admit Black students until seven years later — rejected his application because of his race. In 2017, Duke invited Caldwell to speak in its chapel to help reckon with its past.

Caldwell ultimately went to Boston University School of Theology, where he met many of the fellow clergy who helped shape his ministry — including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Caldwell first met King in 1958, when the civil rights giant returned to his alma mater to give a speech. King already was nationally famous for his leadership of the Montgomery, AL, bus boycott, and Caldwell was vice president of the theology school’s student association. The two would later march together in 1965 to protest school segregation in Boston.

Caldwell was also among the clergy and laity who answered King’s call to come to Selma, AL, after police and others attacked more than 600 peaceful marchers on what became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Caldwell joined in the subsequent march to Montgomery that helped lead to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

At Boston University School of Theology, Caldwell also met clergy who joined him in pushing to integrate the Methodist Church, including the future Bishop White.

The two met when White was a first-year student and Caldwell had just graduated. They would work together to dissolve the Central Jurisdiction and champion equality as staff members of The United Methodist Church’s then-new Commission on Religion and Race.

Caldwell later became a board member of PFLAG, a secular civil rights group whose name initially stood for Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays.

“I considered Rev. Caldwell a real role model for how to do the work within faith communities, and within communities of color,” Jean Hodges, the group’s former national board president, said in a statement. “As a Methodist — and the mom of a gay man — I was moved and inspired by all that he did to bring more allyship and engagement within the UMC.”

Bishop Karen Oliveto said in an email to the Mountain Sky Conference that Caldwell “understood the intersectionality of oppressions long before others were talking about it, always standing with the marginalized to extend God’s love and justice in the world.”

Oliveto, the denomination’s first openly gay bishop, leads the conference where Caldwell served before retiring from pastoral ministry in 2001.

In 2014, on the eve of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, Caldwell officiated at a same-gender wedding even though doing so violated church law and could put his clergy credentials at risk.

In recent years, he eagerly took on the task of telling younger generations about the civil rights movement and helping people understand the progress still needed. He was a prolific writer — authoring four books and publishing articles in multiple outlets, including the Boston Globe and UM News.

“Rev. Caldwell often described himself as a journalist at heart. He valued the power of journalism to increase understanding, speak truth and bring healing,” said Tim Tanton, who directs UM News. “In the last commentary he wrote for us, he expressed concern about the assaults on journalism today and said those who love the Bible should do more to defend journalistic truth. UM News has lost a friend, and our hearts go out to the Caldwell family.”

Caldwell collaborated with Marilyn Bennett, a white lesbian and fellow activist, on the 2016 documentary “From Selma to Stonewall: Are We There Yet?”

“Whoever came into contact with him could take something away,” Bennett said. “He gave a lot of people hope.”

He also worked to pass the torch of social justice advocacy to new United Methodist leaders. One of those is the Rev. Nathan Adams, lead pastor of Park Hill United Methodist Church in Denver, where Caldwell served before his retirement.

“He has forever left his mark on Park Hill UMC as he championed and led our congregation to be the inclusive, community-focused and social justice-minded church it is today,” Adams said.

Caldwell had long worked to change the church from within, and he was greatly saddened at the prospect that the denomination’s debate over LGBTQ inclusion would lead to a church split.

“He experienced personally the hatred of racism, but never failed to express love,” his friend Messer said. “His great disappointment was that The United Methodist Church failed to lead the world in dismantling racism and overcoming homophobia.”

However, Caldwell also never lost faith that the church could manifest God’s love and found hope in this year’s renewed movement toward racial justice.

Caldwell told UM News in June that although, like King, he would not get to the Promised Land with his Black family and allies, he believed if people “keep these moments alive, a semblance of MLK’s ‘Beloved Community’ will be visible.”

He is survived by his wife of more than 60 years, Grace; sons Dale and Paul; and granddaughter Ashley.

Last Updated on October 27, 2023