For the Rev. Bill Arnold, the debate is about what church unity looks like and how the denomination lives into its mission statement. “I consider institutional unity a minimum,” he said.

Their conversation was a preview of what many United Methodists expect to be the most passionate and difficult debate at the 2016 General Conference ─ determining how the denomination ministers with gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people.

Bigham-Tsai, Arnold and Benz were among the speakers at a pre-General Conference briefing that drew some 400 delegates and other United Methodists to the Oregon Convention Center on Jan. 20-22. During the gathering, United Methodists also tested an alternative process proposed by the Commission on General Conference for discussing legislation dealing with tough issues.

The commission and others in the church are trying to find a different way to build consensus in the debate that has raged in the denomination for more than 40 years.

The United Methodist Book of Discipline, the denomination’s book of law, since 1972 has proclaimed that all people are of sacred worth but the practice of homosexuality is “incompatible with Christian teaching.” The denomination bans the performance of same-sex unions and “self-avowed practicing” gay clergy.

The debate has intensified in recent years as more jurisdictions and nations, including the United States, legally recognize same-sex marriage. More United Methodist clergy, including a retired bishop, have officiated openly at same-sex weddings and some United Methodists have raised the possibility of a denominational split.

At the same time, African bishops have explicitly called on The United Methodist Church to hold the line on its teachings regarding sexuality, especially the one that only affirms sexual relations in monogamous, heterosexual marriage. Bishops do not vote at General Conference but their guidance can shape discussion.

At the 2016 General Conference, delegates can choose to apply an alternative “Group Discernment Process” to any of 99 petitions.

“The 99 pieces of legislation are about LGBTQ people ─ not human sexuality. This is about human beings,” said the Rev. L. Fitzgerald “Gere” Reist II, secretary of the General Conference.

Parameters of the debate

Benz explained what she sees as the stakes of the church debate.

She spoke of a Nigerian gay man who found asylum in the United States after being threatened by his brother and tortured by police. She told of a 14-year-old boy who sent an anonymous e-mail to a United Methodist pastor. The boy wrote that he was considering suicide because he could not shake his attraction to boys and believed God hated him.

“What we do as a church, what we do as General Conference delegates, has life-and-death consequences,” Benz said. She is a General Conference delegate from New York and founding member of Methodists in New Directions, an unofficial advocacy group. She is also gay.

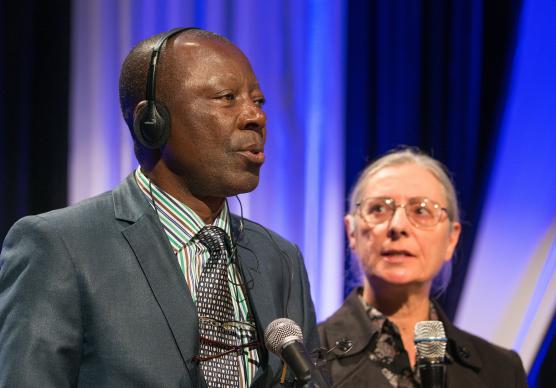

Stanislas Kassongo, a delegate from the Democratic Republic of Congo and a professor of medical ethics, offered a different take.

“In my tradition, the subject of sexuality is taboo,” he said through an interpreter. “That means this subject is only discussed in a family, but really in the midst of the couple.” He added that he did not discuss sex with his five children, four of whom are now married.

What the church teaches about sexuality he sees as God-ordained and in no need of further discussion.

Arnold, a delegate from Kentucky and Old Testament professor at Asbury Theological Seminary, noted that United Methodists are united in deploring violence and sharing doctrine.

But what he’d like to see is a stronger form of church unity. He is a backer of the Covenantal Unity Plan, which includes proposals to strengthen penalties for those convicted of chargeable offenses, as well as making it easier for clergy and congregations that disagree with church teachings to leave the denomination.

Benz said she is happy to affirm unity amid theological diversity. “What I wish we could get to is a genuine theological diversity that doesn’t translate into prosecution and punishment of a minority,” she said. “What I don’t understand is why that persecution is necessary for people who don’t agree with us to have their own theological integrity.”

The Rev. Kennetha Bigham-Tsai, a member of the Connectional Table from West Michigan, explained how the church leadership body developed legislation it hopes can be “A Third Way” in the debate. The Connectional Table’s proposal essentially decriminalizes homosexuality in church law. If it passes, clergy would not risk church trials or the loss of their credentials for officiating at same-gender weddings or, in some conferences, coming out as openly gay.

Bigham-Tsai, a district superintendent, noted she still visits churches that do not want a woman pastor in a denomination where women have had full clergy rights for 60 years. She sees that as a sign of hope — that the denomination is holding together despite some profound differences.

How the alternative process works

To go forward with the alternative discussion process, General Conference delegates will need to approve rule changes when they meet May 10-20, 2016, in Portland.

Immediately after a session on Christian conferencing, participants at the pre-General Conference briefing were given a chance to try out the alternative system using a “mock” piece of legislation. Sitting at round tables, small groups were presented guidelines for conversation aimed at respectful listening and language. They got the legislation and a small group process sheet to work through the process, which is based on the principles of Christian conferencing.

Bishop Christian Alsted, who leads the Nordic and Baltic Area, led the earlier session on Christian conferencing. Church leaders pray the spirit of Christian conferencing will imbue General Conference.

Alsted said that Christian conferencing should be used throughout the denomination’s highest governing body to exercise leadership on all actions.

“It’s not just a method or process to be used at certain times on certain issues. It is more than polite disagreement, it’s not a feel good way to be together, nor has it been a way to come together. It’s a Wesleyan way of being church in the world,” Alsted said.

“Christian conferencing is a means of grace,” he said. “God is always present and conveys his grace when we practice.”

John Wesley asked, “Do we not converse too long? Is not an hour enough?”

“Imagine if we only had one hour to settle our business. What priorities would be made?” Alsted asked.

At the end of the briefing, Reist reported the results of the alternative process test. He said “there was no support for change at this time.”

He noted one of the teams did not return a report and there were several questions for clarification.

Call for unity

Whether delegates opt for the alternative process remains to be seen, but there is no question many church leaders are hoping to prevent the debate from damaging the church’s mission.

Throughout the briefing, participants heard calls for the church to remain unified ─ if not necessarily uniform ─ and for church members to extend grace to each other.

“My prayer, my value, is that our theology of grace … will permeate our conversation,” Arnold said at the beginning of his remarks. “If I take a position or I say something you feel is hurtful, please assume that as best I can see in my heart it doesn’t come from a place of hate but rather it comes from a place of love.”

The Rev. Jean Hawxhurst, who works for the denomination’s ecumenical office, warned during opening worship Jan. 22 that infighting and disunity hurts the United Methodist “witness of salt and light.”

“It’s hurting our influence on culture,” she said, “and making people like my brother think there is no hope because we’re just like everyone else. That is hurting our witness of Jesus’ love.”

Last Updated on January 30, 2024