As of Feb. 8, an estimated 42.5 million COVID-19 vaccinations have been administered in the U.S. United Methodist churches and organizations are helping in the effort to immunize the nation.

HEATHER HAHN

UM News

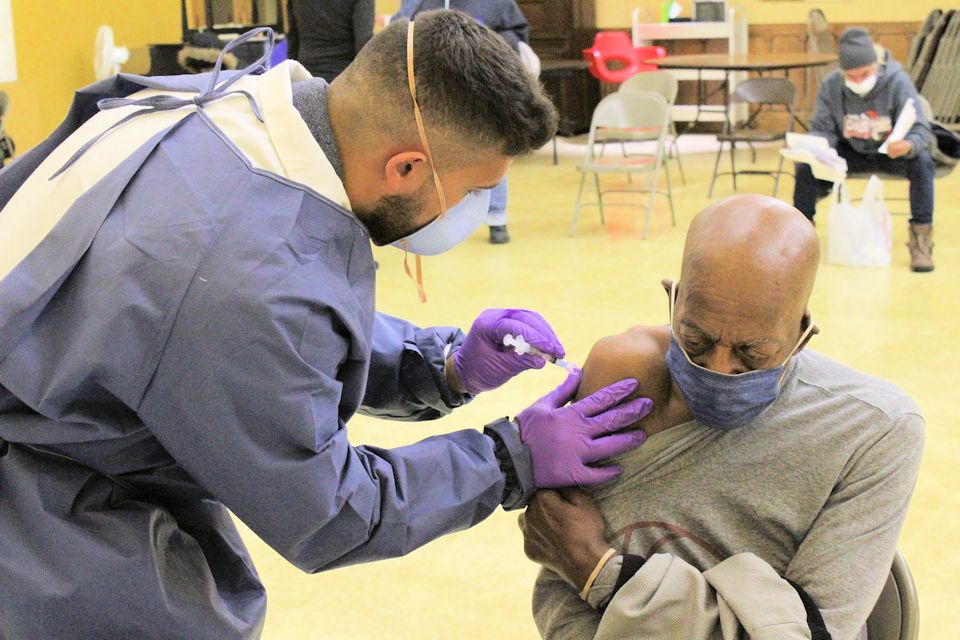

Each weekday since the year started, older adults have poured into a United Methodist church in southern Indiana.

They don’t have to wear their Sunday best, but they all have to roll up a sleeve.

Community United Methodist Church in Vincennes, IN is working with its county health department to distribute the COVID-19 vaccine. The church has moved its food pantry and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings so its recreational center can serve as a daily clinic.

“Anything we can do to help the community to get through the COVID and help relieve some of the stress and the worry, that’s what we want to do,” said the Rev. Darren Williams, the church’s pastor. “Everybody at the church is all for it and very excited to help.”

The Vincennes congregation is not alone. Across the United States, United Methodist ministries are not throwing away their shot to help immunize people against the disease that so far has claimed more than 446,000 American lives.

In St. Louis, Beloved Community United Methodist Church lobbied Missouri’s state health department to be a distribution site for its largely African American neighborhood.

“You hear on the news that many African Americans are apprehensive about this,” said the Rev. Kevin Kosh, the church’s pastor.

“But you don’t have a successful model that points to the fact that many people within the African American community would want to take the shots, but they don’t see it being done through ministries that they trust.”

With help from local African Methodist Episcopal and AME-Zion churches, Kosh persuaded the state to make Beloved Community that model.

People responded. On Jan. 23, the church hosted vaccinations for more than 300 seniors, and the church plans to host the same group later this month for the second round needed for inoculation.

Kosh said the seniors started lining up at 6:30 a.m. for the clinic, which wouldn’t start for another two hours. He made sure the warm church sanctuary was open for all who waited.

At the head of the line was Mrs. Ollie Stewart, an 88-year-old church member. She still lives on her own, but she helped get the word out at a local senior center where many of the residents do not have internet access or, in some cases, even the telephone.

“We served the community well,” she said after the event.

About 80 miles west of St. Louis, leaders of Hermann United Methodist Church in Missouri’s rural Gasconade County immediately stepped up when the county health department asked — with only two days’ notice — if the church could host a vaccine distribution for 180 older adults.

“We will be available whenever they need us to be available,” said the Rev. John Hampton, the church’s pastor.

He acknowledges that the church’s commitment comes with uncertainty. The reason for the most recent late notice was the county received a supply of vaccine it wasn’t expecting. “They don’t know when they’re getting another batch,” Hampton said.

The vaccine rollout has been uneven across the United States. States prioritize different populations; communities have varied ways of handling appointments. Health workers all struggle to ensure vaccine recipients get the two doses required by both the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. As of Feb. 3, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control reported that less than 2% of Americans — about 6.4 million people — had received both doses.

At Community United Methodist Church in Indiana, health workers have been vaccinating about 100 people a day. However, the church has space, and the county has the personnel to distribute more doses if there was more supply, said Betty Lankford, Knox County’s COVID-19 nurse and clinic coordinator.

The church has ample parking, wheelchair accessibility, a kitchen where health workers can eat, and enough space to allow the needed social distancing, Lankford said.

“We are overjoyed that they offered this facility,” Lankford said. “It’s the ideal place.”

The church clinic also does not lack for demand.

In Detroit, the NOAH Project has been working with the city to inoculate a harder-to-reach population, the city’s homeless.

NOAH stands for Networking, Organizing and Advocating for the Homeless. Detroit’s Central United Methodist Church started the ministry initially to provide a bag lunch to anyone who came to the church doors. Now, the NOAH Project is a separate nonprofit, but it still offers daily meals and social services at the church.

Amy Brown, the executive director, said the nonprofit had been doing COVID-19 testing since the early days of the pandemic. She warned that vaccinating her clients would take time, even though they are some of the most vulnerable.

“When we first had a clinic, some people just wanted to watch,” she said. “Our hope is that when the health department comes to offer the second vaccine, they are also able to offer another round of the first vaccine and do this over the next few months because it’s going to take a little bit for people to trust that it’s OK.”

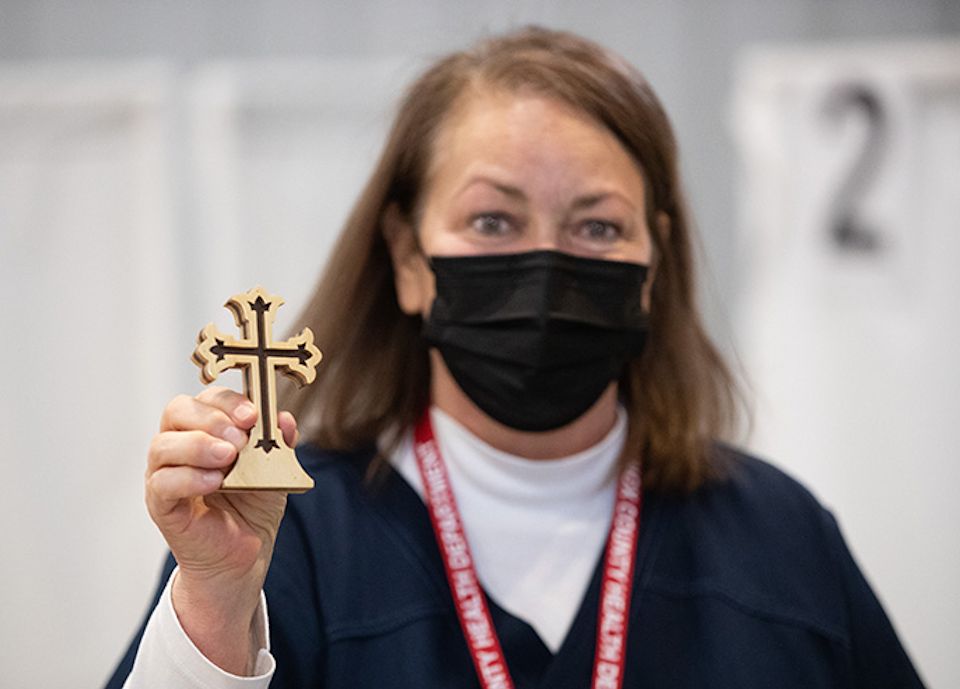

Park Hill United Methodist Church, a multiracial congregation in Denver, is also trying to build trust.

The church is working with SCL Health, a Catholic healthcare organization, to organize a Feb. 6 mass-vaccination event to reach traditionally underserved populations.

The Rev. Nathan Adams, the church’s lead pastor, said his hope is that the church can set an example, especially among communities of color, “that we trust the scientists, health care workers, researchers and leaders who have been working on the vaccine.”

Robin Ridenour, a United Methodist deaconess and faith community nurse, is registering and confirming people’s appointments for the event.

“The Park Hill UMC community is truly amazing,” she said. “Everyone came together to reach out to the elderly and those who are homebound even before COVID.”

As a result, she said, the church quickly filled its 130 slots and has a waiting list of more than 100 if anyone cancels.

In promoting public health, these churches follow a Methodist tradition that goes back to John Wesley himself.

Methodism’s founder made health care a primary focus of his ministry and set up the first free public clinic in London, which he ran until it became too expensive for his limited resources. Later, when yellow fever infected thousands in 1793 Philadelphia, two Black Methodists led the epidemic response.

More recently, one of the early champions and organizers of childhood immunizations in the U.S. was Betty Bumpers, former Arkansas first lady, and a lifelong United Methodist.

However, the United States has never seen the kind of mass-vaccination effort now underway to stop COVID-19.

More churches stand at the ready to help when needed.

Bishop Thomas J. Bickerton has submitted to New York a list of 57 New York Conference churches as potential vaccination sites. However, the state has not yet called upon their assistance.

For now, Community United Methodist Church continues with its plans to inject hope as well as vaccine.

Williams recounted how one 71-year-old woman, upon learning that she could get a shot, burst into tears of relief.

“After the fear and anxiety that has been building up for almost a year, people are looking for answers,” Williams said. “Obviously, the Lord is the first place to go, and if the Lord can use us and anybody else, that’s what we want to do.”

Last Updated on October 31, 2023